The article analyzes the scenarios of the emotional state of invidia that could accompany the experience of visitors to the country villas of the Roman nobility. On the basis of literary evidence the presence of multidirectional tendencies in the attitude to envy as a way of stimulating rivalry within the elites is revealed, which allows the possibility of a conscious desire to induce it through visual architectural techniques, especially perspective. On the material of the poem Statius, the images of symbolic control exercised by architecture and its owners over the states of natural elements are considered. The comparison with architectural techniques in the Villa San Marco reveals a number of perspectives in the deep part of the villa, transmitting the idea of control, while the perspectives united by the theme of envy are in the rooms of the entrance group.

Copyright © 2024 Vyacheslav G. Telminov. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

uring the Late Republic and Early Principate, the private estates of the Roman nobility (domus, villa sububana and villa marittima) were not only places for otium, but also spaces for political negotium: a place to receive a variety of guests , as well as a venue for discussion and political decision-making. These houses and villas, or more precisely, residences, were suitable for hosting a large number of guests and served as a status tool to demonstrate the taste and wealth of their owners.

If any communication needs a space to take place in, political communication tends to take place in public setting. Despite the private status of such villas, the spaces in which this communication took place thus acquired the status of a public one. The public, representative space and the private space within the villa coexisted not chaotically, but following certain structural principles, including the principle of a visual axis.

Wallace-Hadrill formulated the concept of a frontal visual axis that united the main public and private spaces of the house along the public-private vector and thus showed a certain perspective of social (in relation to society) and clientele (in relation to the owner) mobility. In our opinion, this thesis should be extended, at least with regard to seaside villas, by adding lateral perspectives that could evoke other meanings and associations for visitors besides social and clientele mobility.

Previously, on the material of Villa San Marco we have identified possible suggestions (messages) that accompanied the itinerary of different categories of its visitors . This previous study concluded that the most frequently recurring suggestions are grouped around the concepts of envy (invidia) and control (imperium). These two new types of perspectives complement the previously formulated concept of a single axis and thus integrate our understanding of the symbolic landscape of a Roman seaside villa.

If the host would strive to stimulate useful aspects of emotions in his visitors, then from the point of view of the perceiving subject there had to remain a certain freedom of perception. Invidia could be felt not only as a positive emotion (as a claim to a new status, as an emotion evoking the desire to imitate the villa owner and develop cooperation with him for mutual benefit), but also as a negative one. The imperium demonstrated in the villa could also be interpreted both as control over nature, demonstrating the power of the owner, and as inappropriate abuse of his power and trampling on nature in an inappropriate way.

The study of visual axes and the suggestions transmitted by them is impossible without contextualizing the emotion invidia within the framework of ancient usus, as well as analyzing the role of the concept of control within the framework of ancient worldview. Since the problem of envy as an emotion in ancient Roman society has not previously received close attention in science , we will focus on it in this article.

There are two methodological approaches to the study of emotions in science: cognitivist and neo-Darwinist . Cognitivists argue that physiological sensations, which we commonly call emotions, are only a consequence of the brain’s response to sensory and other stimuli. Their opponents believe that the physiological response arrives immediately, even before the brain comes up with the desired interpretation. In this article, we will proceed from the cognitivist approach.

Of all the emotions, pan-cultural emotions are considered the most convenient to study, identified in children of all cultures based on the analysis of facial expressions. These include rage, fear, happiness, sadness, surprise and disgust . As we can see, envy is not among the basic emotions.

Klein stands apart from the rest of the researchers on this issue. She included jealousy in this list and, moreover, called it a primary emotion, associating it with the child’s frustration at the phase-out of breastfeeding against the background of the continuing need for milk from the child . In addition, Klein combined jealousy within the Oedipus complex and longing for mother’s milk into one emotional system.

Most researchers disagree with Klein and consider more complex emotions (envy, jealousy, etc.) to be secondary, i.e. conditioned by the social environment. They appear in children only after acquaintance with the social rules of behavior in a particular culture. Another feature of more complex emotions is that they may include admixtures of primary emotions: for example, jealousy may include fear and rage, and guilt – fear and sadness .

Thus, the study of the manifestations of envy in antiquity has to overcome not only the problem of non-articulated sources, but also the fundamental elusiveness and ambiguity of this emotion as such. In Greek, envy could be described through the terms phthonos and zelos .

Sanders identified an important limitation that arises when trying to study envy on the basis of ancient texts. Phtonos was perceived (indeed, as it is often perceived now) as an unworthy emotion, and therefore those who felt this emotion did not admit to it . On the other hand, this label was well suited for discrediting an opponent. Thus, the identification of this emotion is greatly complicated.

As a methodology for analyzing the invidia emotion in ancient Rome, it should be reasonable to replicate Sanders’ approach. He identified scenarios (typical situations) of manifestation of emotional states that fit the concept “envy”. He examined these texts through the prism of scientific findings of modern psychology, assuming that the cognitive nature of human beings remains unchanged. The author uses Aristotle’s text as an ancient benchmark to correct possible distortions due to the extensive use of modern psychology. In Latin, the concept of envy has a clear visual connotation – it is conveyed by the verb invidere and its derivatives. In explanatory dictionaries, the meaning of certain aspects of this concept is also conveyed through visual images. For example, in Lewis and Short’s Latin-English dictionary invidia is translated as follows: “to look askans at; to look maliciously or spitefully at; to cast an Evil Eye on” .

Let us first consider at the basic conceptual level the forms of manifestation of this emotion in the context of a visit to a Roman villa, the visual axes of which emphasized wealth, prestige, refinement and power of the owner.

According to the most commonly used definition, envy is an emotion felt in situations of lack of a desired object. Psychologists, sociologists and anthropologists envy to be a complex social emotion arising in the conditions of comparing oneself with other members of society. The initial stage of development of this emotion includes 3 stages of perception :

1) That someone else possesses some thing or quality

2) That I don’t have this thing or quality

3) That this situation is unfair

The presence of this reasoning in the sources can serve as preliminary indicators for invidia. In the situation of visiting a Roman villa by different categories of guests, variations related to stages 1 and 2 must have been in place by the logic of natural human experience. As a rule, the hosts in the Roman world of hospitality have a higher position than the guests, unless we are talking about equal friends of the host – but even in this case particular villas and their interior were unique and unrepeatable, so that even a peer could answer positively to the questions of the first two points.

What about the third point? It is the one that plays a determining role in causing the perceiver of inequality to begin to feel envy.

According to Sanders, self-esteem is directly proportional to the feeling of injustice. The higher the self-esteem, the higher the subjective feeling of the right to claim the benefits that cause envy. There is also a directly opposite opinion of Rawls, linking these two states in an inverse relationship , as well as Ben-Zeev’s opinion that there is no correlation between them .

Finally, according to Sanders, envy is more likely to arise in a situation of comparison between two people of equal status. Here he relies primarily on Aristotle and his doctrine of emotions .

What emotions does envy consist of? Since it is a complex emotion, according to psychologists it can be divided into several parts. Thus, Spielman divides envy into the following elements :

Sense of competition (including admiration)

“Narcissistic wound” (feelings of belittling, wounded ego, humiliation, disappointment in oneself)

A greedy desire either to destroy the object of envy, thereby harming the opponent, or to appropriate the property for oneself

Fury

These basic components of envy are also indicators when present in conjunction with the above-mentioned indicators.

Roman society clearly tried to combat invidia by prohibiting the display of luxury . These measures were aimed not at wealth per se, but at its display during feasts, public processions, during the construction of baths intended for the public , i.e. in the public field . If we consider these efforts from the perspective of modern science, the conclusions are disappointing: many psychologists are convinced that the mere reduction of social contrasts can reduce the overall level of envy, since envy is most often directed at people of similar status .

Let us now consider invidia cumulative scenarios that take into account the above indicators. Sanders identifies 5 general scenarios of envy for ancient Greece :

I feel the desire to deprive you of a boon, but I don’t want to possess it myself (gloating envy)

The desire to deprive you of a good is stronger than the desire to possess it yourself (greedy envy)

The desire to possess is stronger than the desire to deprive you of the good (greed)

I feel the desire for a similar benefit, but I do not want to deprive you (imitation)

I don’t want to do anything to deprive you of the benefit, but I keep feeling envy (imitative envy)

This list of scenarios, in our opinion, can be replicated to Ancient Rome without limitations. In the context of our study, it makes sense to consider only positive scenarios 4 and 5. Based on basic rationality, it is difficult to assume that negative scenarios could have been deliberately incorporated into visual perspectives.

Let us first analyze scenario 4: “I feel the desire to obtain a similar good, but I do not want to deprive you”. This scenario can also be characterized as a stimulus and a process of imitation, which makes one seek a similar good and thus leads to both positive results from the point of view of Roman society (rivalry, ambition) and negative ones (adornment, the desire to increase luxury and wealth, to make dust in the eyes of one’s compatriots).

In the 2nd century BC. Cato expectedly condemned senators for decorating their villas . But since then, by the time of Cicero, much had changed. Marzano notes that villas were not only a way to confirm the fact of belonging to the Roman elite, but also a symbol of the desire to become its member . In this context, envy could acquire a positive meaning – this may explain the fact that invidia is included in the list of emotions that a speaker, according to Cicero, should be able to excite in his listeners . Cicero’s complex attitude to envy is further illustrated by passages like the discussion of a wise person’s attitude to emotions in the Tusculan Conversations . Here Cicero brings compassion and envy closer together: “If a wise man were subject to grief, he would also be subject to compassion and envy (invidentia) – I do not say ’hatred’ (invidia), which happens when one cannot see another’s happiness; but from the word ’see’ one can without ambiguity also derive the word ’envy’, which happens when one looks too much at another’s happiness (…) As compassion is grief for another’s misfortune, so envy is grief for another’s happiness. He who is subject to envy is also subject to compassion; the wise man is not subject to envy, therefore neither is he subject to compassion” .

However, already in the next book of Tusculan Conversations Cicero toughens his criticism of envy and begins to define it as “grief from another’s prosperity, which does not harm the envious person in any way” . At the same time, imitation, i.e. the desire to obtain what the envious person does not have, is already unambiguously defined negatively – as “rivalry in bad things (’jealousy’), in which a person wants what he does not have and another has it” . In the end, Cicero rejects imitative envy even more unambiguously: “To envy another is also to compete, only more jealously; what is the use of it, if the whole difference is that the rival longs for another’s good, which he does not have, and the envious person longs for another’s good, because the other has it too?” .

An illustrative example of imitative envy (Scenario 4) is found in Sallustius, although he himself distances imitation from envy: “Our ancestors, the senatorial fathers, never lacked either prudence or courage, and pride did not prevent them from adopting other people’s customs, if they were useful (…) whatever their allies or even their enemies possessed and which seemed to them suitable, they applied most assiduously to themselves; they preferred to imitate good things rather than to envy them” .

Cicero’s philosophical generalizations are supported by more specific judgments about his contemporaries. Thus, Cicero condemns Lucullus for setting a bad example to his neighbors by building a luxurious villa , that is, setting an example of elite construction to others through envy. It is also quite indicative that in ancient Roman public discourse there was a realization that luxurious buildings are useful when intended for public needs (and then it is magnificentia), but are not permissible for private purposes – as luxuria .

Thus, we can see that scenario 4 was not always perceived as positive by the Romans themselves, but it was not interpreted as unambiguously negative, which left room for debate and speculation, and potentially allowed villa owners to consciously seek to arouse this emotion in their guests.

Finally, let’s discuss scenario 5: “I don’t want to do anything to deprive you of wealth, but I continue to feel envy”. This emotional scenario is most likely to occur in the lower strata of Roman society, which had much fewer opportunities to achieve a similar level of prosperity as the nobility, thus could not emulate or realistically try to reach the same level of wealth.

In one of his texts, Horace speaks of the unenviable fate of a rich man, who cannot be truly pleased by anything, even though his luxurious villas are stirring envy among the common people. Let’s pay attention to the fact that the word invidendis characterizes new technologies and styles of construction used in villas: “Why should I erect an atrium with columns and in a new sublime style that excites envy? Why should I change my Sabine valley for the burdensome riches?” . It is clear from this fragment that Horace was aware of the capacity of architectural means for impressing visitors, and, more importantly, that these methods were criticized as improper.

Seneca’s reasoning in the Moral Letters falls very neatly under the characteristics of Scenario 5: “Leave riches – they are either dangerous to the owner or burdensome. (…) Leave the search for honors – it is hubris, empty and fickle thing, there is no end to it, it is always on the alert to see if there is someone ahead, if there is someone behind, always tormented by envy, and a double envy for that matter. You see how unhappy a man is if he who is envied is also envied. Do you see these houses of nobles, these thresholds where those who come to worship quarrel noisily? You will suffer insults to enter, and even more when you do. Go past the rich man’s staircases and the embankment-raised vestibules: there you will stand not only on the steep, but also on the slippery place. Better direct your step here, toward wisdom: strive for the peace it gives, for its abundance!” .

It would be logical to expect Seneca, in the spirit of Stoicism, to divert the problem from envy to compassion, emphasizing that the nobles, towards whom it is customary to feel envy, regard their lot as unenviable and long for their precarious position at the top of the slippery social ladder. But let us pay attention to the context in which Seneca places his philosophical maxim: the lobbies and atriums of expensive houses and villas, from which staircases (and, we must add, following Horace, columns and walls decorated with colorful frescoes) ascend to the upper floors. As a result of considering these scenarios, we can state that the villa environment could, under certain conditions, induce emotional states that can be characterized as invidia.

This article concludes with a look at the symbolic control of nature and related suggestions and emotional states in visitors of Roman villas.

Marzano notes that by the first century BC, villae maritimae had become a metaphor for the control exercised by humans over nature and a symbol of civilization in the natural environment . Architecture carries a huge civilizing component and thus can symbolically express the power of man or society over space . This should be particularly pronounced in liminal spaces, which are themselves the battleground of several elements – sea, air and earth, as, for example, on the seashore. Placed in this context, the villa, which dominates both land and sea, is an ideal image of control (imperium), uniting under its symbolic power the sea, the mountains and the heavens.

Purcell proposed a classification of types of control over nature – interference in the seascape by building bridges, pontoons, promenades; control over river water by building canals, waterfalls and other objects of garden and park design”; finally, control over height by building villas on high hills, rocks, creating terraces, etc. . Note that the idea of controlling the sea element fits into the context of Rome’s struggle for dominance on the sea routes, especially the trade routes supplying Italy with grain .

Let us consider one very revealing poetic work that speaks about several aspects of the symbolic control of architecture (and its owners) over the forces of nature. In one of the poems of the Silvae collection of poems, Statius praises the power of a roman elite member through the description of his villa that dominates the sea. In the text of the poem, phrases about power, control, subjugation and transformation are a constant refrain: “domuit possessor”, “domat saxa aspera dorso”, etc.

The villa owner and the architecture created on the orders of this man thus control the sensory landscape, subdue nature, transform it according to the tastes of the owner.

Further, the poet notes that the rooms face different sides which, accordingly, implies the owner’s “control” over the temperature of the rooms : “This room sees the first rays of the sun, and that one catches the sunset rays, // Preventing the midday heat of the strongest light “.

The architecture and its owner also exercise control over the sounds of the sea by drowning out the noise of the waves: “The sea murmurs silently, but under the roof you can’t hear // the sound of the surf – the silence of the land makes your ears happy. // Having blessed the terrain, nature has yielded to art // And, receptive, has adapted to new rules” . According to Statius, not only light, heat and the sounds of the surf have submitted to man, but even the landscape itself has yielded to his inexorable pressure. Where there was a mountain, there is now a plain; where there was a swamp, there are now buildings: “Having blessed the terrain, nature has yielded to art // And, receptive, has adapted to the new rules. // Here, where you see the plain, there was a mountain; and a swamp // Where you come under the shelter. Do you admire the high grove? // There was no land there: the lord overcame the uncomfortable. // He both builds the cliff and tears it down. Both of them are good for the earth. The rocks are accustomed to bear the yoke, // The mountain submissively retreats before the buildings come” .

And where the landscape has not changed, architecture has settled on the rock and thus demonstrated its dominance: “A winding portico climbs up the rock // You can say that it is a city! – and the rocky cliffs humble their stiffness” .

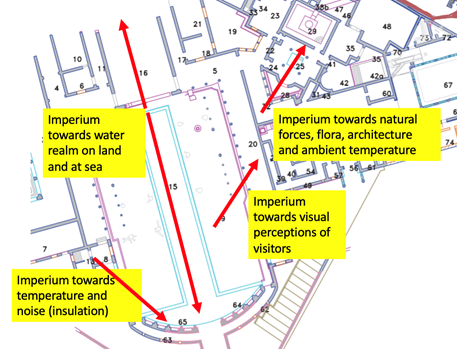

To conclude, here are examples of visual perspectives and suggestive objects in a Roman villa that could embody and broadcast to visitors the idea of control over the natural elements, including the plant kingdom . In the Villa San Marco (Figure 1) there are three groups of objects that fit these characteristics:

1) visual axis through room 28 (viridarium) and the frigidarium of the thermal complex (25) .

2) visual axis uniting the sea view, the ceremonial triclinium 16, the long pool 15, and the nymphaeum (65-64) .

3) Finally, the illusionism of the peristyle wall paintings, which, by mirroring the peristyle grove ( with plane trees), amplify the visual sensations of the real garden and thus express the idea of controlling the visual sensations of visitors , and especially the cryptoportico (rooms 62-63), also fit into the category of “controlling” architecture. The cryptoportico could embody the idea of controlling the temperature of the environment and noise, as it kept the air cool on a hot day while also dampening sounds coming from the sea or the surrounding households . Protected from external influences, noise, rain, wind and heat, the cryptoporticus allowed one to experience the isolating control of architecture by the design and will of its owner.

We can conclude, that the perspectives and individual rooms symbolizing the idea of control (imperium) are mostly grouped in the most closed part of the villa, while the perspectives inciting envy are found in the more public part of the villa (atrium columns, staircases at the entrance, visual axes leading to the peristyle, etc.). We now have at our disposal further confirmation of the hypothesis of a social conditioning of the visual perspectives found in Roman villas. The farther away from the entrance, the more explicitly the idea of control is actualized, and the less frequent the incitement of envy.

At the same time, we cannot exclude the following interpretation – the main symbolic meaning and intention of any visual perspectives was to arouse envy, but different methods of influence were required for different groups of visitors. For lower social groups, the greatest envy could be aroused by the luxury of decoration, high columns and visual axes showing the sheer size of a villa. But for the nobility, the signs of luxury and the scale of construction were no longer sufficient to arouse imitative envy (the desire to compete), and so, as one moved from the entrance to the villa to the peristyle and cryptoporticus, there was a gradual transition to another type of suggestion, namely, control over the forces of nature, landscape, and sensory perception (imperium). Thus, both envy and control come to a common denominator, although they demonstrate different approaches to solving a single communicative task within the Roman villa.

Having analyzed the scenarios of the emotional state called invidia in antiquity, which best suited the context of the visual and psychological experience of villa visitors, we came to the conclusion of the validity of including invidia among the suggestions symbolically embodied in visual perspectives. The texts show an ambiguous attitude towards envy, interpreted as a possible stimulus for imitation, and thus having the potential for social, i.e. useful, application in Roman society, where rivalry within elites and ambition were a socially approved norm. In the second part of the paper, fragments of Statius’ poem were examined, in which images of the symbolic control of architecture (and its owners) over the natural elements were reflected. The identified images of control were then juxtaposed with the perspectives in Villa San Marco. Invidia suggestions of scenario 5 tend to be found at the beginning of the visitors’ itinerary (and include rooms accessible to visitors from lower social groups). Imperium suggestions, on the contrary, were revealed in the deeper parts of the villa, where groups close to the owner in terms of their status and condition could be accepted. In addition, there is a possibility of combining both suggestions within a single intension – if we interpret imperium as a way to solve the same communicative task, but in relation to social groups closer to the owners of the villa.

This paper was written in 2023 and funded through the grant of Russian Science Foundation (project No. 22-78-00133).