The acceptance of technology at the higher educational level has been a significant discussion, with little attention on the gender dynamics on the acceptance of artificial intelligence (AI ) tools by senior lecturers. This study delved into a detailed analysis of the gender dynamics in the discussion of technology acceptance mainly AI tools, in foreign language (FL) education. Quantitative study approach was adopted in the process, and survey design was implemented. Data was collected using structured digital questionnaire, based on the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT) model. A total of ninety-five (95) male senior lecturers and one hundred and three (103) female senior lecturers participated in the study. Analysis was conducted using relevant statistical measures. The results showed disparities in the attitudes and views of senior lecturers towards artificial intelligence (AI) technologies in the context of FL education, greatly influenced by gender. In relation to usage, male senior lecturers have higher positive reactions (61.06%) in comparison to their female counterparts (46.6%). However, in relation to the assumption that AI technologies improve the performance of learners, 69% of male senior lecturers agree with this notion, but a substantially greater percentage of 72.81% of female senior lecturers hold the same perspective. Moreover, there exists a little disparity in the level of proficiency in using AI technologies across genders. Specifically, 56.84% of male senior lecturers see it as uncomplicated, while 61.16% of their female counterparts share the same sentiment. The gender discrepancy that is most notable pertains to the perceived level of ease in using artificial intelligence (AI) technologies during foreign language (FL) lessons. The data reveals that a majority of male senior lecturers, calculated as 69.48%, see the use of these tools very easy. In contrast, a much higher proportion of female senior lecturers, 86.41%, share the same perception. This discrepancy highlights a notable disparity in confidence levels between the two genders. These results together emphasise the changing gender dynamics in the acceptance of technology, interrogating conventional assumptions and underscoring the need for customised support systems to guarantee fair and efficient integration of artificial intelligence (AI) technologies in foreign language instruction among senior lecturers.

Artificial intelligence (AI) innovations, such as chatbots and advanced language processing algorithms, are being increasingly used to contribute to educational experiences. The established backdrop forms the foundation for a comprehensive examination of the perceptions and integration of artificial intelligence (AI) technologies in the teaching techniques of senior lecturers, particularly within the realm of foreign language studies. The research is especially interested in the fascinating environment of foreign language classrooms due to the distinctive challenges and possibilities encountered by lecturers in this setting [1-3].

An essential component of this research examines gender disparities in the acceptance of artificial intelligence (AI) among the senior lecturers. The study of gender dynamics has been extensively examined across several disciplines, although its connection to the acceptability of technology in educational environments has received less attention [4]. Gaining insight into the responses of male and female lecturers towards AI tools is of utmost importance, as it may provide valuable guidance for the design and integration of these technologies. By engaging in this practice, it promotes the advancement of educational technology and pedagogical approaches that are inclusive of all genders. Additionally, the results of this study have the potential to provide valuable insights to educational institutions and legislators on the need for specialized training initiatives, supportive structures, and available resources that effectively address the varied requirements of lecturers. The research has the potential to improve the overall quality of foreign language instruction by integrating technology improvements with the preferences and acceptance levels of senior lecturers. This alignment would contribute to the creation of a more effective and inclusive learning environment.

An innovative step towards the future of education is the use of artificial intelligence (AI) in educational settings. Artificial Intelligence (AI) technology has established itself as a mainstay in contemporary education (thanks to its ability to alter teaching and learning processes). Intelligent tutoring systems, immersive virtual reality settings, and adaptable learning platforms developed by AI all respond to the demands of the individual student, improving the quality of education as a whole. Al-Emran, Elsherif, and Shaalan [5] demonstrate the usefulness of AI in mobile learning apps by manifesting how well they provide tailored and engaging learning experiences. Due to AI’s flexibility, teachers may design individualized learning pathways for their students, guaranteeing that they get education that is relevant to their needs and that will help them retain information.

Artificial intelligence (AI) technologies have brought about revolutionary developments in foreign language education. According to studies by Blake Soleimani, Ismail, and Mustaffa [6], and Al-Awawdeh et al. [7], technology-driven language learning applications have made revolutionary language learning techniques available. These programs use AI algorithms to provide individualized language training, immediate feedback, and rich language experiences. As a result, students may practice their language in a way that seems natural and relevant, which improves both their conversational abilities and overall competency. AI has a significant global influence on education [2,8]. In varied cultural and linguistic situations, research by Alfarani [9] highlights the benefits of AI-powered teaching. Artificial intelligence (AI) technology integration has filled in educational gaps and opened up high-quality education to students from all socioeconomic and geographic backgrounds. This international reach guarantees that students from different backgrounds may profit from AI-driven learning resources, fostering inclusion and equality in educational possibilities.

The impact of AI also includes addressing gender differences in teaching languages. In their studies on lecturers’ post-COVID-19 behavioral intents, Khong et al. [10] stress the value of AI-driven platforms in fostering inclusive learning environments. Teachers may accommodate to different learning demands by customizing their teaching strategies using AI, successfully addressing the problems that are unique to gender. Students may overcome linguistic hurdles via individualized learning experiences made possible by AI, enabling them to flourish in their language studies. The use of AI in language instruction also results in the development of cutting-edge evaluation tools. In their study of the gender inequalities in the use of game-based learning in online EFL classes, Almusharraf et al. [11] demonstrate many uses of AI in language evaluation. In addition to measuring language competency, these game-based tests also make the evaluation process fun and participatory. Lecturers may successfully modify their teaching tactics by gaining deep insights into their students’ linguistic ability using AI-driven exams [12-17].

The incorporation of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in foreign language teaching has been the subject of in-depth study, showing how language teaching is changing. In a similar vein, Jung and Lee [18], investigated how well-liked YouTube is among teachers and students, highlighting the potential of AI-enhanced video platforms for language learning. AI-driven chatbots and virtual assistants have revolutionized language practice in addition to immersive experiences. An et al. [19] investigated middle school English lecturers’ behavioural intention to utilize artificial intelligence (AI), emphasizing the value of chatbots powered by AI in language learning. Additionally, a study by Salem [8] examined how Libyan professors perceived the usage of technology in the classroom while demonstrating how AI-driven technologies were included to improve language teaching approaches.

Extensive number of studies have focused on the gender dynamics surrounding the acceptance of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in foreign language education. These studies highlight the subtle variations in technology acceptance that occur across different genders. A considerable volume of research has been dedicated to investigating the domain of gender disparities in the use of technology [20-24]. These studies have provided insights into the divergences in the acceptance, usage habits, and attitudes towards technology shown by male and female lecturers. A review of these studies provides significant perspectives on the fundamental elements that contribute to these discrepancies.

The topic of gender disparities in AI usage has been thoroughly explored in several studies, such as the research undertaken by Li and Kirkup [25] and Ramírez-Correa et al. [26]. These studies provide a fundamental comprehension of the disparities in technology acceptability among male and female users. The available data indicates that society and cultural standards, together with gender roles, have a substantial influence on peoples’ perspectives and beliefs on technology. Hence, these aforementioned criteria have an impact on the level of acceptance of artificial intelligence (AI) applications within educational settings, specifically in the context of foreign language classes. In addition, previous studies conducted by Saleem, Al-Saqri, and Ahmad [27] as well as Cahyani et al. [28] have delved into the evaluation of lecturers’ technology pedagogical and content knowledge (TPACK). The aforementioned research places significant emphasis on the convergence of pedagogy, subject comprehension, and technological expertise, highlighting the potential impact of gender-related disparities in these areas on the acceptance of artificial intelligence (AI) in educational settings. Female lecturers may encounter certain problems or exhibit distinctive teaching styles that might influence their engagement with AI-driven educational technologiesc[29-32] . It is essential to comprehend these distinctions in order to develop artificial intelligence (AI) programs that effectively appeal to lecturers of both genders.

Furthermore, scholarly investigations conducted by Prescott [33] and Jenson and Rose [34] have explored the perspectives of lecturers towards certain technology resources. This research demonstrates that lecturers’ views of technology are often influenced by gender biases and power dynamics. Female lecturers may face distinct expectations and encounters when it comes to the use of technology, in contrast to their male colleagues [35-37]. As a result, differing degrees of acceptance for technology-driven utilization are expected from the lectures with different genders. The mitigation of these biases may be achieved by the implementation of focused interventions and awareness campaigns, which aim to cultivate an inclusive atmosphere conducive to the integration of artificial intelligence (AI) in language teaching.

In addition, Huang, et al. [3] as well as Khong et al. [10] have conducted research on the topic of lecturers’ self-efficacy in relation to the integration of technology. The said research provide evidence that individuals’ self-perceived ability in using technology has a substantial influence on their acceptance and patterns of utilization. The potential disparities in self-efficacy across genders may be attributed to cultural norms and the extent of technological exposure, which might impact the inclination of female lecturers to use artificial intelligence (AI) applications. To rectify these inequities, it is imperative to implement customized training programs and establish support systems that enable female lecturers to effectively use the whole capabilities of artificial intelligence (AI) in language education. Furthermore, the investigations carried out by Aruleba, Jere, and Matarirano [38] as well as Saleh and Jalambo [39] have scrutinized educational situations in the aftermath of the pandemic situation. The COVID-19 epidemic exacerbated pre-existing gender gaps in technology acceptability, as seen by the abrupt transition to online and technology-driven education. Female lecturers, particularly those who are balancing several responsibilities, may have significant difficulties when it comes to adjusting to teaching techniques that heavily rely on technology. It is important to comprehend these problems to foster the creation of inclusive artificial intelligence (AI) applications, so safeguarding against the marginalization of female lecturers in the process of digitizing education.

The examination of technology acceptance models has played a crucial role in comprehending the complexities associated with lecturers’ acceptance of technology, specifically Artificial Intelligence (AI) technologies, in educational settings. Numerous well-known models, such as the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) and the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT), along with their various iterations, have been widely utilized and modified to investigate the determinants that impact teachers’ acceptance of technology. These models have yielded significant findings and valuable perspectives on the integration of AI tools in the field of education.

The Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT) has been employed by many studies in the analysis of technological acceptance in different areas. The study conducted by Abd-Rahman et al. [40] explored the use of flipped classroom by senior ESL lecturers. The study employed UTAUT, using the four main units (performance Expectancy, PE, Effort Expectancy, EE, Social Influence, SI, and Facilitating Conditions, FC). The study unveiled the diverging views of the lecturers on the acceptance values of the tools. The study conducted by Salem [8] also explored the use of UTAUT in technology acceptance in the primary educational system. The study highlighted the importance of technological advancements in the primary education system. There are more studies that have integrated UTAUT in exploring technology acceptance, but none has focused on the use of the model to explore gender divergence in the acceptance of technology among senior lecturers in FL education/instruction.

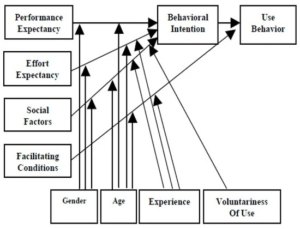

This study makes use of the UTAUT paradigm to analyse the acceptance of technology among lecturers. The primary objective of this investigation is to measure the degree to which gender inequalities exist in acceptance levels. The UTAUT model offers a conceptual framework for gaining an understanding of and explaining the adoption and utilisation of technology. According to Figure 1, the researchers that were responsible for developing the model came up with the unified theory of technology acceptance and use of technology (UTAUT) model, which has three separate components and the social influence.

Performance expectancy (PE).

Effort expectancy (EE).

Facilitating conditions (FC).

The term “performance expectancy” refers to the extent to which a person, specifically a lecturer in the context of this study, perceives that the use of technology will contribute to the attainment of certain academic teaching objectives within a normal university setting. According to the proponents of the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT), performance expectation emerges as the most influential construct among the four components included under this theoretical framework. This idea on acceptance models has also garnered support from other scholars. Therefore, the incorporation of performance expectation within the framework of this research indicates that foreign language (FL) lecturers are likely to see artificial intelligence (AI) learning aids as valuable resources for facilitating the instruction of the English as a foreign language. Effort expectation refers to the level of ease that is connected with the use of a system. There is a prevailing belief that a construct centred effort is anticipated to be more salient during the first phases of adopting a novel habit. Therefore, the adjustment of effort expectation within the framework of this research indicates that foreign language (FL) lecturers would see artificial intelligence (AI) learning aids as user-friendly when incorporating them into their teaching practices. The concept of social influence may be characterized as the extent to which a person considers significant individuals to have the belief that they ought to adopt the new system. This framework pertains to the notion that an individual’s conduct is shaped by their perception of how others will see them as a result of their use of technology. The significance of social elements becomes even more important in instructional settings. Facilitating circumstances pertaining to the extent to which a person holds the belief that there is an established organizational and technological framework in place to facilitate the use of a system. These four characteristics have a crucial role in forecasting the level of acceptance among foreign language teachers towards artificial intelligence (AI) systems.

This paper used the quantitative research approach in exploring the nature of gender dynamics in acceptance and integration of technological advancements in foreign language teaching and learning. The choice of quantitative study approach is to be able to gather numerical data based on the four major components of the UTAUT model, which are the Performance Expectancy (PE), Effort Expectancy (EE), and Facilitating Conditions (FC). The survey design strategy was sued in the designing the study pattern and the data collection systems.

The study community include lecturers that have been in the profession for the last decade and half. In other words, the lecturers must have been teaching foreign languages for at least 15 years, which covers the period through which AI tools have developed extensively and applied in foreign language pedagogy. They are referred in this study as senior lecturers, instead of ‘older lecturers’, mainly to ensure that a wider age spectrum is captured in the research.

The research included several public and private universities. As randomized sampling technique is the most time- and cost-effective design for vast geographic regions, it was utilized to choose universities because it was uncertain how many FL lecturers were employed at the selected universities. The study’s sample size was calculated using Cochran’s formula. The reason Cochran’s formula was employed is that it enables investigators to calculate the sample size based on their chosen degree of accuracy, acceptable level of confidence, and the percentage of the features in a population. When estimating unknown sample sizes, Cochran’s formula is more often utilized than other models. As a result, 198 senior lecturers at different universities were the estimated sample size according to the procedure. The table below summarizes the demographic variables of the study population.

Table 1 provides a thorough description of senior lecturers in foreign language instruction, including details on their professional backgrounds and demographics features. Notably, there is an equal proportion of male and female lecturers among the participants, indicating a wonderfully balanced gender distribution. This equal distribution of genders is important because it guarantees a variety of viewpoints when it comes to comprehending the acceptance and application of AI technologies in language learning environments. It implies that the perspectives and experiences of both male and female senior lecturers will influence the study’s conclusions, offering a comprehensive knowledge of artificial intelligence acceptance in the context of gender dynamics. A very modest but significant population, 7.06% of participants had over 20 years of expertise, indicating a group of highly experienced teachers. Their broad experience probably includes a number of changes in educational technology, so their perspectives are especially helpful in figuring out how technology acceptance – including AI – has changed over time.

| Category | Variable | Frequency | Percentage |

| Gender | Female | 103 | 52.02% |

| Male | 95 | 47.98% | |

| Age | 40 years or less | 19 | 9.59 |

| 41-50years | 47 | 23.74 | |

| 51-60years | 96 | 48.49 | |

| 61-70years | 36 | 18.18 | |

| Years of Experience | 14 years | 5 | 2.53 |

| 16-20years | 179 | 90.41 | |

| More than 20 years | 14 | 7.06 | |

| Academic Rank | Senior Lecturers | 28 | 14.15 |

| Associate Professors | 79 | 39.89 | |

| Full Professors | 91 | 45.96 |

The data demonstrates a fair distribution of academic rank across various levels. Nearly 40% of senior lecturers are Associate Professors, despite 45.96% of them having the prestigious title of Full Professor, which denotes a high degree of authority and experience. This suggests that there are a significant number of seasoned lecturers who although are not yet holding the highest academic title, have a wide breadth of expertise. Furthermore, 14.15% of the participants are Senior Lecturers, which offers insightful perspectives from experienced lecturers who may be at a different stage in their careers. The participation pools with wide range of academic backgrounds, guaranteeing a rich variety of viewpoints, from mid-career professionals to very eminent professors. This variety is essential for capturing a wide range of perspectives, experiences, and difficulties regarding senior lecturers’ acceptance and integration of AI technologies in the context of teaching foreign languages.

A written permission letter was created by the researchers and linked to the online survey in relation to data collection. Subsequently, the researchers spoke with a single FL professor from every department or faculty to distribute the questionnaire link to all other FL lecturers in that department or institution. Later, the representatives used their authorised school emails, and the WhatsApp programme to transmit the link to their colleagues involved in FL. teaching. For the online survey, the researchers created a link, and Google Forms was used to create the questionnaire. If participants wanted to send the researchers any private feedback or suggestions, a short explanation of the questionnaire’s goal and the researchers’ contact information were supplied. There was no deadline provided by the researchers for responders to finish their questionnaire. But, before responders could finish the questionnaire, the researchers needed approximately thirty days for the survey to be completed. The UTAUT survey questions from Abd-Rahman et al. [40] were used in the development of the questionnaires.

The data was analysed using relevant statistical measures, including the computation of the values of the responses, which was based on Likert scale values of agree, neutral and disagree. The mean, and the standard deviation were also computed in the descriptive statistics tables.

The following research questions are submitted in guiding the study.

How do lecturers’ acceptance and integration of technological advancements in FL differ based on gender using Performance Expectancy (PE)?

How do lecturers accept AI tools in FL based on gender differences, using Effort expectancy (EE)?

In what ways do male and female senior lecturers view facilitating conditions (FC) in the acceptance of AI tools in FL?

The result is presented in this section, together with a detailed discussion of the findings, which also reflects the implications of the findings. As such, the section is further segmented into result and discussion.

The results are presented in accordance with the three research questions, which makes the section to run in different subparts.

The UTAUT model is primarily built on the understanding of the participants performance expectancy in the use of the technology, the effort expectancy, and the facilitating conditions. These are the three bases on which the results are submitted in the following tables.

| Question Items | Agree | Disagree | Mean | Std. Dev |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male Senior Lecturers | ||||

| I find AI tools very useful for teaching FL | 61.06% | 38.94% | 3.44 | 2.02 |

| I find using AI tools for teaching FL will enhance performance of learners | 53.69% | 46.31% | 3.27 | 2.17 |

| I find it very easy to be tech-savvy at using AI tools in FL lectures | 56.84% | 43.16% | 3.29 | 2.09 |

| I find AI tools easy to use in FL lectures | 69.48% | 30.52% | 3.76 | 1.98 |

| Senior Female Lecturers | ||||

| I find AI tools very useful for teaching FL | 46.6% | 53.4% | 3.14 | 2.25 |

| I find using AI tools for teaching FL will enhance performance of learners | 72.81% | 27.19% | 4.28 | 1.72 |

| I find it very easy to be tech-savvy at using AI tools in FL lectures | 61.16% | 38.84% | 3.86 | 1.93 |

| I find AI tools easy to use in FL lectures | 86.41% | 13.59% | 4.88 | 1.62 |

Following an in-depth review of the extensive data shown in Table 2, it becomes apparent that there are notable disparities in the attitudes and views of senior lecturers towards artificial intelligence (AI) technologies in the context of FL education, which are influenced by gender. In relation to usage, male senior professors have somewhat a higher level of favourable disposition (61.06%) in comparison to their female colleagues (46.6%). However, in relation to the assumption that AI technologies improve the performance of learners, a noticeable disparity based on gender becomes apparent. Specifically, 53.69% of male senior lecturers express agreement with this notion, but a substantially greater percentage (72.81%) of female senior lecturers hold the same perspective. This disparity highlights a significant divergence in the perception of effectiveness across genders. Moreover, there exists a little disparity in the level of proficiency in using AI technologies across genders. Specifically, 56.84% of male senior lecturers see it as uncomplicated, while 61.16% of their female counterparts share the same sentiment. The gender discrepancy that is most notable pertains to the perceived level of ease in using artificial intelligence (AI) technologies during foreign language (FL) lessons. The data reveals that a majority of male senior professors, i.e., 69.48%, see the use of these tools very easy. In contrast, a much higher proportion of female senior lecturers, amounting to 86.41%, share the same perception. This discrepancy highlights a notable disparity in confidence levels between the two genders. These results together emphasise the changing gender dynamics in the acceptance of technology, questioning conventional assumptions and underscoring the need for customised support systems to guarantee fair and efficient integration of artificial intelligence (AI) technologies in foreign language instruction among senior lecturers.

| Question Variables | Agree | Disagree | Mean | Std. Dev. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male Senior Lecturers | ||||

| I find it difficult to teach FL courses without using AI tools | 34.73% | 65.27% | 2.39 | 2.22 |

| I find AI tools in FL appealing to me when my colleagues use it | 46.31% | 53.69% | 3.06 | 2.09 |

| I will likely teach more topics in FL if I use AI tools to facilitate the process | 72.63% | 27.37% | 4.73 | 1.23 |

| Female Senior Lecturers | ||||

| I find it difficult to teach FL courses without using AI tools | 74.75% | 25.25% | 4.82 | 1.06 |

| I find AI tools in FL appealing to me when my colleagues use it | 88.34% | 11.66% | 5.07 | 0.73 |

| I will likely teach more topics in FL if I use AI tools to facilitate the process | 94.18% | 5.82% | 5.62 | 0.39 |

Upon careful analysis of the extensive data shown in the Table 3, a detailed depiction of the gender dynamics surrounding the acceptance of artificial intelligence (AI) technologies among senior lecturers in FL becomes apparent. The observed differences in the perceived effort expectation are rather evident. Specifically, it is noticeable that 34.73% of male senior lecturers have difficulties in teaching foreign language (FL) courses without the assistance of artificial intelligence (AI) tools. In contrast, a much higher proportion of female senior lecturers, amounting to 74.75%, also express similar challenges. This discrepancy highlights a noteworthy disparity in the perceived need of AI tools in the teaching of FL courses between male and female senior lecturers. This disparity is further amplified inside social settings, whereby the desirability of AI technologies experiences a notable surge when used by coworkers. In this study, it was shown that 46.31% of male professors express a positive inclination towards the use of AI tools in collaborative settings. Remarkably, a far higher percentage of female lecturers, amounting to 88.34%, share this attitude. This finding highlights the considerable effect of peer opinions on the acceptance of technology, particularly among women. The gap reaches its highest point when considering the inclination to expand the range of instructional subjects via the integration of artificial intelligence (AI). Among male senior professors, 72.63% demonstrate a similar predisposition, while a far higher proportion of female senior lecturers, specifically 94.18%, indicate a proactive position towards embracing technology as a means to enhance pedagogy. This highlights their strong enthusiasm for incorporating technological advancements into their teaching practises. These results collectively illustrate a scenario in which female senior lecturers demonstrate a greater dependence on and enthusiasm for artificial intelligence (AI) tools in the context of foreign language (FL) education. This challenges conventional gender norms and emphasises the pressing requirement for customised support systems to address the disparity in technology acceptance between genders. The significant disparity shown underscores the need for educational establishments to recognise and confront these intricate gender dynamics, guaranteeing a nurturing and all-encompassing atmosphere for higher-ranking lecturers, promoting fair integration, and augmenting the entire educational encounter in foreign language classes.

The third research question also seeks to unveil how the facilitating conditions in technology acceptance differ on gender basis among the senior lecturers. The collected data are summarized in the table below.

| Question Variables | Agree | Disagree | Mean | Std. Dev. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male Senior Lecturers | ||||

| I have the resources necessary to use AI tools in my FL classes | 76.84% | 23.16% | 4.85 | 0.94 |

| I have the knowledge and digital skills necessary to use AI tools in FL education | 46.31% | 53.69% | 3.05 | 2.13 |

| The university where I work provides necessary assistance for the use of AI in FL teaching. | 32.64% | 67.36% | 2.45 | 2.21 |

| Female Senior Lecturers | ||||

| I have the resources necessary to use AI tools in my FL classes | 86.41% | 13.59% | 5.27 | 0.69 |

| I have the knowledge and digital skills necessary to use AI tools in FL education | 96.11% | 3.89% | 5.94 | 0.32 |

| The university where I work provides necessary assistance for the use of AI in FL teaching | 37.86% | 62.13 | 2.59 | 2.03 |

With an established basis in UTAUT’s “Facilitating Conditions,” Table 4 presents an intricate overview of gender dynamics in senior lecturers’ acceptance of AI technologies in FL. The differences are especially noticeable when it comes to the accessibility of essential resources. While 76.84% of senior lecturers who are male, accept that resources are available, 86.41% of their female colleagues agree, indicating a considerable gender difference and stressing the urgent need for equal resource distribution. Examining digital abilities reveals a sharp contrast: just 46.31% of senior lecturers who are male feel competent, indicating a significant ability gap. Conversely, a remarkable number, i.e., 96.11% of female senior lecturers report, feeling confident and indicating a significant skill gap. These results highlight how important is it to provide focused training that focuses on improving digital capabilities, particularly for senior male lecturers, to create an equitable environment for technology. A lack of institutional support, which is critical for the use of technology, is evident, especially for female senior lecturers. Only 37.86% of female teachers feel that universities assist them, as compared to 32.64% of male lecturers. This discrepancy highlights an important area for development, motivating organisations to enhance support systems designed to address the particular difficulties experienced by female senior lecturers. These nuanced findings highlight how important is it for educational institutions to give equal resource distribution, gender-sensitive training programmes, and increased institutional support top priority to foster an inclusive environment where senior lecturers of all genders can succeed in the digital FL education space.

The results underscore a clear indication of gender dynamics in acceptance of (AI) technology in FL, mainly using the UTAUT model (PE, EE and FC). The findings are narrowed to answer the three research questions. In the first research question focused on the performance expectancy, the results are summarised in table 4. As the first survey question from table 2 is considered within the context of UTAUT’s PE, where the results reveal fascinating insights. A positive perspective was shown by the finding that 61.06% of male senior lecturers deemed AI technologies to be extremely beneficial. On the other hand, only 46.6% of the female senior lecturers felt the same way. The variation may be attributed to the perceived usefulness of AI tools, which is in line with the results of Henderson et al. [41], who emphasised the significance of perceived usefulness in determining the level of technological acceptance among professors. The disparity in responses highlights the need of investigating gender-specific variables that influence perceived usefulness, as was noted in earlier research [26].

The results are notable when considered in light of the question 2 presented in Table 2, which relates to the performance expectation of UTAUT. While just 53.69% of male senior lecturers felt that AI technologies improve learners’ performance, a substantially larger proportion of female senior lecturers asserted likewise (72.81%). This indicates that female senior lecturers are more likely to hold this opinion. This discrepancy may be due to gender differences in the ways in which people perceive the efficiency of AI technologies in improving student achievements. Previous research [42] has shown that the perceived effect on performance is a crucial factor that plays into how people react to new technologies. According to research conducted by Li and Kirkup [25], female senior lecturers are more likely to have a strong conviction in the beneficial effects of artificial intelligence (AI) technologies. This finding is consistent with the changing gender roles as well as the rising number of women working in disciplines connected to technology.

Taking a look at the responses to the third question in Table 2 through the prism of UTAUT’s PE reveals some intriguing patterns. About 61.16% of female senior professors agreed that it was simple to be tech-savvy, which is a larger proportion than the 56.84% of male senior lecturers who said they found it easy to be tech-savvy. These results contradict conventional gender preconceptions related to technical ability and consistent with the developing gender dynamics in the acceptance of technology Ramrez-Correa et al., [26]. The findings highlight the need of doing research into the elements that contribute to these views, particularly in light of the rapidly changing environment, surrounding the use of technology in educational settings.

When taking into consideration the last survey question in Table 2, in the context of UTAUT’s performance expectation, responses demonstrate significant disparities according to gender. In comparison, only 69.48% of male senior professors considered AI technologies to be simple to use, in contrast to the considerable majority of female senior lecturers (86.41%). The results of Zekiye [43] are echoed by this gender discrepancy in perceived ease of use, which underscores the effect of gender-specific characteristics on technological acceptability. According to Li and Kirkup [25], female lecturers have a greater level of self-assurance when it comes to employing AI technology tools. This might be ascribed to the flexibility and readiness of female lecturers to accept new technologies. This is in line with the shifting landscape of gender roles in technology acceptance.

These gender-specific disparities in attitudes and views towards artificial intelligence (AI) systems in foreign language instruction have major implications. Educational institutions have a responsibility to acknowledge the varied points of view held by senior lecturers and to design professional development programmes in accordance with these considerations. It is possible that acknowledging and resolving these discrepancies can lead to more successful training programmes, which will promote a supportive climate in which lecturers, regardless of gender, can comfortably incorporate AI technologies into their teaching practises. Additionally, our results add to the larger conversation on gender dynamics in the use of technology, highlighting the need for continuing study to guarantee inclusive and equitable technology integration in education.

The second research question focuses on the effort expectancy of the UTAUT model. The results are contained in Table 3. The analysis of the responses in Table 3 provided by senior lecturers, categorized by gender, with regard to effort expectation within the framework of the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT), provides valuable insights into the gender-related aspects of technology acceptance in the field of FL education. The first item in the table highlights a notable disparity between male and female senior lecturers in their use on AI technologies for teaching foreign language (FL) courses. According to the data, a significant proportion of male professors (34.73%) report, facing difficulties in teaching without the assistance of AI technologies. Similarly, a considerable majority of female lecturers (74.75%) share this attitude. The observed gender gap indicates that female senior lecturers see AI tools as an essential aid, highlighting the crucial role that technology plays in their teaching methods. The findings presented in this study are consistent with other research that highlights the significant influence of effort expectation on the acceptability of technology [22].

The data further indicates that the allure of artificial intelligence (AI) technologies in the context of FL education is more pronounced when used by colleagues, hence accentuating the contrasting experiences between genders. According to the data, it is seen that a significant proportion of male lecturers, amounting 46.31%, express their inclination towards using AI technologies in collaborative environments. In contrast, a much higher percentage of female lecturers, equal to 88.34%, also have a similar perspective on the matter. The results of this study align with the observations reported by Li and Kirkup [25], indicating that social influence plays a substantial role in the acceptance of technology, especially among female lecturers who show a greater inclination towards collaborative technology utilization. Moreover, the significant disparity highlights the impact of peer relationships, suggesting that the acceptance of AI technologies is heavily influenced by social environments.

The last question item in Table 3, “The utilization of AI tools to facilitate the process would likely result in teaching a greater number of topics in FL,” shows a significant gender imbalance. A notable proportion of female senior professors (94.18%) demonstrate an overwhelming preference towards expanding their teaching capacity by including artificial intelligence (AI) technology. Similarly, a substantial percentage of male senior lecturers (72.63%) show a similar disposition. These results of Henderson, Selwyn, and Aston [41] are reinforced by these data, emphasizing the crucial significance of perceived ease and usefulness. The data suggests that female senior lecturers have a greater propensity for embracing artificial intelligence (AI) technologies, which reflects their proactive stance in response to the evolving dynamics of gender roles in the use of educational technology.

The implications of these results are diverse and complex. In the first place, it is essential for institutions to acknowledge the varied demands and preferences of senior lecturers, and therefore design training programs that cater to the special issues encountered by female lecturers in the realm of technological integration. Furthermore, recognizing the significant impact of peer interactions underscores the need of cultivating a collaborative and supportive atmosphere whereby lecturers may exchange their experiences and skills. Furthermore, the acknowledgement of the proactive approach taken by female senior lecturers in adopting technology is a significant change in gender dynamics. This movement challenges conventional standards and promotes inclusivity in the use of technology in foreign language education. The significance of gender-specific nuances highlights the need for ongoing research and customized support systems to promote fair and efficient integration of artificial intelligence (AI) technologies in FL teaching for senior lecturers.

Research question 3 focuses on the facilitating condition, and the findings are summarised in table 4. The analysis of the data in table 4, from the perspective of UTAUT’s ’Facilitating Conditions’ framework reveals clear indications of gender dynamics among senior lecturers in the acceptance of artificial intelligence (AI) technologies in the context of FL education. Regarding the availability of resources for the integration of AI tools, male senior lecturers demonstrate a moderate degree of accessibility, as shown by a consensus agreement of 76.84%. In contrast, it is noteworthy that a substantial majority of female senior professors, amounting 86.41%, express their agreement about the accessibility of crucial resources, therefore indicating a notable disparity when compared to their male colleagues. These results are consistent with earlier studies that emphasize the significant influence of resource availability on the acceptance of technology [39]. The presence of a significant gender disparity underscores the need for educational institutions to allocate resources towards promoting equal opportunities for senior lecturers, so enabling them to successfully incorporate technological integration. A notable gender difference becomes evident when assessing the acquisition of information and digital skills necessary for using artificial intelligence (AI) systems in the context of foreign language instruction. A significant disparity in skill levels is seen among male senior lecturers, as only 46.31% of them express confidence in their possession of the requisite abilities.

The acceptance of technology at the higher educational level has been a significant discussion, with little attention on the gender dynamics on the acceptance of AI tools by senior lecturers. This study delved into a detailed analysis of the gender dynamics in the discussion of technology acceptance mainly AI tools, in foreign language (FL) education. Quantitative study approach was adopted in the process, and survey design was implemented. Data was collected using structured digital questionnaire, based on the Unified Theory of Technology Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT) model. A total of 95 male senior lecturers and 103 female senior lecturers participated in the study. By examining how male and female senior lecturers evaluate, use, and incorporate AI technologies into their teaching techniques, a deep literature study laid the groundwork for understanding the intricate interaction of gender dynamics in technological acceptance.

Following a closer review of the study’s results, an intricate representation of gender-specific concerns and views emerged. The data highlighted important aspects including performance expectation, effort expectancy, and facilitating conditions, based on UTAUT framework. It also showed clear differences in male and female senior lecturers’ acceptance of AI tools. Female senior lecturer demonstrated a deeper dependence on and excitement for AI technologies, analysing conventional gender norms and highlighting the pressing need for customised support systems. The differences highlight the need for academic establishments to recognise and tackle these complex gender dynamics, guaranteeing a nurturing and all-encompassing atmosphere for senior lecturers, promoting fair integration, and augmenting the comprehensive learning encounter in FL classrooms. Additionally, a thorough examination of the study’s senior lecturers’ perspectives on digital skills, institutional support, and the availability of AI tools revealed several areas in need of targeted intervention. Comparing female senior lecturers to their male colleagues, wherein the former showed much more confidence in the availability of required resources and in their digital abilities. Nonetheless, a discernible disparity was seen in the evaluation of institutional support, underscoring the need for academic institutions to improve their support initiatives, guaranteeing a comprehensive strategy for incorporating technology. In order to create an inclusive and cutting-edge educational environment, closing these gaps will need specialised training programmes, mentoring programmes, and fair resource distribution.

As a result, this research highlights gender-specific differences in attitudes, abilities, and institutional support, providing insightful information on the complex dynamics of AI acceptance among senior lecturers in FL education. The results highlight the need for educational establishments to promptly adopt focused approaches, emphasising the development of digital proficiencies, distributing fair resources, and optimising institutional support frameworks. Universities can create a climate in which senior lecturers, male or female, flourish in using AI technology by tackling these gender-specific differences. This will enhance the learning environment and equip students for a technologically sophisticated future. In addition to offering a substantial contribution to the body of literature already in existence, this research is also an important catalyst for practise and policy development concerning technology integration in FL education, guaranteeing a more progressive and inclusive learning environment for all parties involved.

The authors extend their appreciation to the Deanship of Scientific Research and Graduate Studies at King Khalid University for funding this work through Large Group Research Project under grant number RGP 2 /170/45