Background: The Saudi higher education system is going through continuous reforms to achieve the goals set by the kingdom’s Vision 2030. To support these reforms, we research the concept of institutionalism by looking into its indicators comparatively between the Swiss and the Saudi higher education systems. Methods: A thematic analysis was performed to identify institutional indicators in organizational practices. A qualitative meta-synthesis approach was then used to identify contributions of these indicators using the PRISMA method. Results: 20 institutional indicators were identified. The contribution of these indicators was narratively synthesized from 199 studies and categorized into 7 main themes. Enactment of these indicators was present in the Swiss Federal Act in a ratio of 17:20, in comparison to a ratio of 5:20 in the Saudi higher education Order. Conclusion: Institutionalism was not found to be strongly built in the Saudi Higher Education Order.

In Saudi Arabia, the higher education system began in 1949 with the establishment of the College of Sharia in Mecca city. Since then, and over a period of more than 70 years, the national five-year development plans were the main guiding instrument for all sectors in the country including Education, and more recently, with the enactment of the country’s vision 2030, this ambitious plan had placed higher education at its core, aiming to build intellectual capital as a cornerstone of national development [1,2].

Reviewing these past development plans, reveals critical indicators of inefficiency in the development journey of the higher education system, a starting example emerged in the third development plan where high dropout and failure rates was presented as a challenge of internal efficiency, which shifted focus in subsequent plans to qualitative improvements [3-6]. And from another perspective, external efficiently emerged also as an additional challenge, that reflected negatively on employment rates and employer satisfaction [7], where plans of mitigation were addressed as well since the third development plan and echoed forward highlighting the need for programs tailored to industry demands [3-6]. All these challenges appear to have hampered the achievement of development plan goals. Indicators like published research, citations, strategic studies, patents, and graduate student numbers, all fall below the expectations outlined in the 2011 higher education strategic plan [7].

Given this context, this paper studies institutionalism as an organizational concept that understands the sociology of organizations with its norms, rules, and ideologies, and how these elements can influence behavior to achieve organizational goals [8,9]. Through this lens, we opt to study the shortcomings of the Saudi Higher Education system by exploring how institutionalism as an organizational concept can build a more robust system that ensures alignment between policy and societal values, paving the way for goal achievement [10].

Drawing on Parsons’s [11] social action system, which sets the core institutional structure of modern society into four subsystems of action: economy, politics, law, and culture, this paper analyzes how the Saudi higher education institutions considers the role of these subsystems to accomplish their designated function of goal attainment as a political function, adaptation to internal and external environments as an economic function, integration within the system as a legal function, and preservation of cultural values as a cultural function. Investigating this prospective is guided throughout this paper by the following research questions:

How can institutionalism facilitate the achievement of Saudi higher education goals?

How can institutionalism enable the Saudi higher education system to adapt to its internal and external environment?

How can institutionalism enable integration of the Saudi higher education system?

How can institutionalism preserve cultural values and norms within the Saudi higher education system?

Institutionalism holds a prominent position in the organizational context. It has gained this position due to the assumption that it is necessary and essential for rationalizing and improving performance, and keeping pace with change [12]. In reviewing the literature on institutionalism, we find that the historical development of its concepts falls under two versions, the first emerged with Selznick’s study published in 1949 [13] entitled “TVA and the Grass Roots.”, and the second showcased with Meyer’s two article published in 1977 entitled “The Effects of Education as an Institution” and the other with Rowan in the same year entitled “Institutionalized Organizations: Formal Structure as Myth and Ceremony”.

Within the realm of organizational analysis, various scholars have focused on diverse aspects of institutional theory. For instance, Selznick [13], Meyer [14], and Meyer and Rowan [15] emphasized cultural norms and ideologies, while Hirsch [16] explored the influence of the political system and law. Ouchi [17] focused on the impact of organizational networks within the market, and North [18] examined the role of economic rules. These examples, along with many others, illustrate the broad and multifaceted aspects to institutional theory in organizational studies [19], posing a sense of ambiguity as a concept with many intellectual contributions yet with no agreement on its specific meaning in organizational context [20].

In the renowned Talcott Parsons Theory of the Social Action System, Parsons proposed four fundamental subsystems that comprise any social unit within the social action system, regardless of size, these subsystems form the institutional structure that ensures the social unit’s stability, survival, and adaptation to environmental changes. They are the political, economic, legal, and cultural systems. Parsons also associated each system with a distinct function; the Political System with Goal attainment, the Economic System with Adaptation, the Legal System with Integration, and the Cultural System with Latency, preserving societal, cultural patterns and values that regulate individual and collective behavior [11]. Through this, Parsons laid the foundation for his influential social action system theory, defining the functional requirements of the institutional structure for any social unit. He termed it the GAIL System, where each letter represents the first letter of each function of the four subsystems.

The political system holds the responsibility of achieving organizational goals. This means, it holds a connection to the formal state authority that sets goals, creates orientations, and directs resources [21], and what institutionalism has developed around this, is an understanding of the role played by actors outside of this formal authority [22]. The political perspective of institutionalism here directs the meaning toward shaping or influencing behavior, power, and political actors’ preferences [23], whether through formal means such as empowering the voice of social actors, enacting governance schemes, and reflecting from international alliances controls, or whether through informal means such as employing power & interest groups as institutional entrepreneurs to leverage their influence in building convergence, conformity, and stability in the institutional structure in service of institutional goals [24-26], or building new institutional logic through the employment of public opinion to legitimize the prevailing rules set by the political entity to achieve organizational goals [21,27], or activating informal governance practices where participation from informal actors is directed towards a pluralist steering approach that is controlled under the formal authority through mechanisms such as acknowledging soft-law and empowering social and professional networks [21,28,29].

Another perspective to institutionalism in the political system is evident by looking into how organizations relate to the everchanging nature of the environment they operate in, and what institutionalism adds here is the adoption of a catalysts view for these changes, for the purpose of maintaining steady adaptation and alignment, whether these changes affect service provisioning measures such as considerations for supply-demand gap or considerations for equality in service between regions and sectors [30], or whether these changes affect operational measures such as physical infrastructure or socio-economic, political, or technical current state [31].

The economic system holds the responsibility of adaptation, and according to the social action system theory, this function is achieved through economic mechanisms that manages resource scarcity [32]. From this perspective, institutionalism is the structure that creates the incentive to shape human action towards economic efforts [33], Such as a strive for efficiency, which shapes the direction of economic effort to obtain the best value for money [34], whether in the form of technical efficiency, being the best possible outcome from the relationship between resources and results; or in the form of productive efficiency, that is the maximization of the results given the same resources, or in the form of allocative efficiency, which considers the larger context of resource allocation and distribution within society [35].

Another institutional perspective in this domain is financial performance, which is identified through two main measures by Saleth and Dinar [30]; the financial gap between expenditure and cost recovery, which looks into “gains in productivity to the public investment in education” [36], a measure that guards service sustainability and continuity [37], and the investment gap between the actual and the required investment, which looks into how investments are set to achieve a certain outcome, a measure that should be based on a clear defined unit such as the cost per students instead of a collective cumulative cost [38], and can be evaluated by monetizing measures such as number of awarded degrees [39], or success of graduates in the market [40], or any other mean that reflects on economic performance such as government effectiveness; one of the six aggregate indicators of governance [41,42].

Another perspective to economic performance is transaction cost, a concept introduced by Coase [43] and defined by North [33] as “the cost of exchange and the cost of enforcing property rights over goods and services”, North [44] identified four main components of transaction costs: the cost of implicit attributes, the cost of enforcement, market size, and the cost of changing ideological positions and beliefs. The cost of implicit attributes is the value of the attributes accompanying the main service, and in the context of this paper, it is the benefits that higher education provides the learner with besides obtaining a degree, the system incurs these benefits at a certain cost, and what is meant here is the value of the cost of these accompanying benefits (implicit attributes). The cost of enforcement is the cost of enforcing property rights over goods and services, i.e., the costs of directing human interaction to prevent rule violations, reporting them, and enacting incentives to avoid them, this cost is low if it is in the other party’s best interest to comply. Market size is the cost of specialization in the transaction sector, such as finance, insurance, and real estate, its cost expands and contracts according to its size. Finally, there is the cost of changing ideological positions and beliefs, which is an informal economic institutional indicator that points out to the cost of moving individuals to embrace new norms and beliefs that drive these individuals to organize economic activities to couple up with the formal instated economic rules [45].

From the same informal perspective, Fiori [46] presents the concept of complementary rules, based on Akerlof’s [47] theory of partial gift exchange, as one of the theories of efficiency and wages in flexible contracts, where “gifts should be more than the minimum required to keep the other party in the exchange relationship” (p. 559), adding power to the institutional economic system from the perspective that formal contract rules set the minimum standard between the two parties, but social norms regulate what goes beyond that, and this area that exceeds the minimum is the area of complementary rules that contracts allow to increase the output of contractual value with behaviors such as additional effort or work by the contractor, which is met with financial rewards or other benefits by the contractor. This theory extends from the ideas of Polanyi [48], who was interested in analyzing the complementary relationships between market rules and social norms since social norms determine in great deal workers’ performance.

The legal system is the system responsible for integration, it holds a holistic formal stand that regulates interaction within various organizational networks by setting the rules and foundations to guide and maintain integration. Saleth and Dinar [30] addressed this in their study from an institutional perspective by proposing three levels from where to measure the effectiveness of integration in the legal system, they are: the level of the public policies, the level of the sector policies, and the level of the administration regularities components. Within these levels, they look at aspects of dispute settlement provisions and accountability provisions within the public policy level, and aspects of the extent to which sector policies are affected by policies of other sectors within the sector policies level, and aspects of functional capacity and technical capacity within the administration regularities level.

An extension to this perspective is the remaining three aggregate indicators of governance that stand out within the integration function due to the relation they impose on institutional quality, they are: rule of law, regularity quality, and control of corruption [41,42]. The rule of law signifies the societal and institutional culture that respects the basic principles of law and equality before it, the rule of law also develops institutional checks and balances on political power [49] and on government performance [50], which in turn improves the regularity quality [51] and enhances control of corruption by creating trust in the government [52].

The last subsystem within the social action system is the cultural system. It holds a function of preserving cultural values within the larger social system, with it, the pillars of the institutional structure come to a complete formation, activating this subsystem requires knowing the patterns of cultural values that the institutional structure must preserve, and the base for this is the individual who resembles the unit of analysis in this structure.

From this perspective, we explored the concept of Habitus [53], which is a “a set of historical relations “deposited” within individual bodies in the form of mental and corporeal schemata of perception, appreciation, and action” [54]. These schemata resembles what Swartz [55] called the “structural cultural matrix”. From this perspective, we look at every action as a product of this matrix, which, from Bourdieu’s point of view, is somewhat resistant to change, because it is rooted in early childhood experiences [55]. According to Reay [56], manifestation of the Habitus shows in patterns of ethnicity, social positions, and collective characteristics to which the individual belongs, such as social class and religious affiliation. By understanding this, the cultural system is able to create an institutional habitus that is in alignment with that of the individuals’ in the social system of which the organization operates. This institutional habitus, as a concept introduced by McDonough [57], refers to organizational practices that support the logic of thought and action in the organizational structure, the alignment of this institutional habitus with the social context is at the heart of institutional theory, as it assumes that the social context in which the organization operates is a power that influences behavior within organizations [15], from the perspective that individuals are the actors who create meaning within this context [58], and who translate these institutional elements to action [59].

From understanding the impact of habitus on the social system, comes another perspective that questions how this habitus can be altered and changed, and how this change can affect behavior, values, beliefs, and leads to the adoption of new cultural patterns that create new rules in the cultural and therefore the institutional structure. The formation of this new cultural patten is what Bourdieu [60] refers to as the cultural capital, it is one of the determinants of the individual’s position in the social space, alongside economic capital and social capital [61]. Cultural capital, according to Bourdieu [62], is what penetrates into the individual’s habitus as an unintentional effect of his external surroundings, and thus adding to the capital that embody the cultural values of this individual [63], this affect is apparent through what means such as media and civil society organizations can create, messages passed through media can plays a significant role in shaping what we know and what we build our options about [64], what we stand for or reject [65], and civil society organizations hold another example of power shaping community beliefs, as they aim to bring about change in a specific direction by influencing the way their target audience think and act [66].

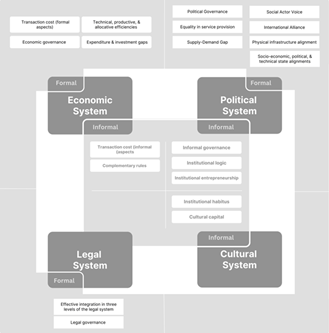

In conclusion of this section, Figure 1 presents an illustration of the institutional structure with all indicators tranced from the four sub-system. 10 indicators from political system, 6 from the economic system, 2 from the legal system, and 2 from the cultural system.

A qualitative meta-synthesis approach was used to systematize the selection and analysis of literature following the methodology outlined by Sandelowski and Barroso [67]. This approach was selected to identify qualitative literature in relation to our research questions, and to guide us through evaluating, summarizing, and integrating evidence to answer these questions by forming new interpretations of the findings in primary studies [68], and presenting them in a narrative synthesis approach as a common approach to present the review of qualitative studies [69].

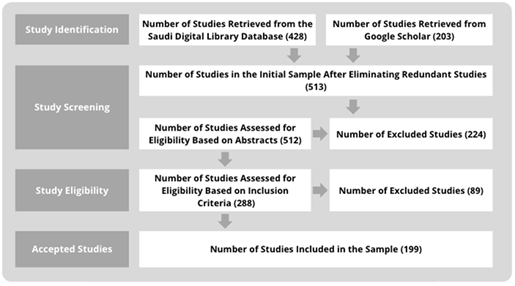

Comprehensive search for relevant studies was conducted in the Saudi Digital Library and Google Scholar with account to three inclusion criteria: 1) the study must be held in the context of higher education; (2) the study must discuss one indicator of Institutional practice as an independent variable; (3) the study must be published in a peer-reviewed journal, by an official body, or in a book. A total of 199 studies were included in the final sample after screening and refining results following the PRISMA flow diagram by Moher et al. [70] showcased in Figure 2.

Data from the 199 articles were extracted and populated in a table (Appendix A) where the following are identified: (1) researcher/s; (2) study title; (3) independent variable (an institutional indicator); and (4) dependent variable. Subsequently, Thomas and Harden [71] thematic synthesis approach was applied where findings from each study was coded into initial descriptive themes, and later developed into main analytical themes where analysis and interpretation were performed to develop understanding of institutional elements in organizational studied that answer our four research questions.

From the reviewed 199 studies, 100 studies were mapped to the first research question, and 70 studies to the second research question, and 16 studies to the third research question, and 13 studies to the forth research question. Along these studies, seven main analytical themes were identified, and under each theme, the main dependent variables are grouped and listed (Table 1), Further, these themes are elaborated on in the next section showcasing the related variables under each.

| Main Themes | Relational Dependent Variables | Number of Studies | |

| 1 | Organizational Order (61 Studies) | Quality of Higher Education Public Policies | 18 |

| Legitimacy and Trust in Higher Education Institutions | 12 | ||

| Sense of Participation Ownership in Achieving Higher Education Goals | 12 | ||

| Public Interest Community Service | 6 | ||

| Operational Performance of Higher Education Institutes | 5 | ||

| Private Sector Participation in Higher Education | 7 | ||

| Foreign Investment in Higher Education | 1 | ||

| 2 | Financial Efficiency (55 studies) | Expenditure Efficiency in Higher Education | 39 |

| Financial Independence of Higher Education Institutes | 10 | ||

| Private Sector Partnership in Higher Education | 6 | ||

| 3 | Economic Growth and Development (24 studies) | Foreign Investment in Higher Education | 2 |

| Regional Development thru Higher Education | 7 | ||

| National Economy support thru Higher Education | 15 | ||

| 4 |

Quality of Higher Education

(22 studies) |

Quality of the Higher Educational Environment | 1 |

| Quality of Higher Educational Outcomes | 8 | ||

| Efficiency in the Learning Process | 13 | ||

| 5 | Standards and Global Trends (14 studies) | University Rankings | 4 |

| Internationalization of Higher Education | 4 | ||

| Sustainability of Higher Education Services | 1 | ||

| Strategic Direction of Higher Education | 5 | ||

| 6 |

Human Development

(12 Studies) |

Competitive Capabilities of Higher Education Graduates | 7 |

| Knowledge Producing and Innovation | 5 | ||

| 7 |

Preserving National Distinctiveness

(11 studies) |

Public Commitment to Social Values Norms | 6 |

| Driving Collective Behavior | 5 | ||

| Total | 199 | ||

Studies that discussed organizational order presented seven main dependent variables that were linked to twelve (12) independent variables (institutional indicators) they are: (1) social actor voice, (2) governance from the political perspective in components of voice and accountability and stability & control of corruption, (3) institutional entrepreneurship, (4) international alliance, (5) alignment with socio-economic, political, & technical states, (6) equality in the provision of higher education service, (7) informal governance in components of soft law and networks, (8) allocative efficiency, (9) transaction cost in its informal measure of the cost of changing positions & believes, (10) effectiveness of integration in the levels of sector policies &administrative regularities, (11) governance from the legal perspective in components of rule of law, regularity quality, & control of corruption, and (12) forming institutional habitus (Appendix A).

Under the financial efficiency theme, three main dependent variables emerged: expenditure efficiency, financial independence, and partnership with the private sector, these variables held relation with eleven (11) independent variables (institutional indicators), they are: (1) governance from the political perspective in the component of stability & control of corruption, (2) alignment with socio-economic, political, & technical states, (3) equality in the provision of higher education service, (4) building institutional logic, (5) institutional entrepreneurship, (6) technical & productive efficiency, (7) expenditure and investment gaps, (8) government effectiveness, (9) transaction cost in all its formal components, (10) complementary rules, and (11) effectiveness of integration in the level of sector policies (Appendix A).

Studies that emerged under this theme presented three main dependent variables; (1) foreign investment in higher education, (2) regional development thru higher education, and (3) national economy support thru higher education. These variables were dependently affected by nine (9) independent variables (institutional indicators), which are: (1) political stability and the absence of violence from the political governance components, (2) equality in the provision of higher education services between regions, (3) alignment with socio-economic, political, and technical states, (4) productive efficiency, (5) investment gap between the actual and the required investment, (6) market size, (7) complementary rules, (8) forming the institutional habitus, and (9) building cultural capital (Appendix A).

This theme was formulated on three dependent variables, they are (1) quality of the higher education environment, (2) quality of higher education outcomes, and (3) efficiency in the learning process. And what drives change in these three variables in our context, are five (5) independent variables (institutional indicators) that are: (1) social actor voice, (2) voice and accountability from the political governance components, (3) international alliances, (4) the gap between supply and demand in higher education services, (5) alignment with socio-economic, political, and technical states, (6) equality between regions, (7) building institutional logic, (8) institutional entrepreneurship, (9) productive & allocative efficiency, (10) and the investment gap (Appendix A).

Studies that presented this theme unveiled four main dependent variables, they are: (1) university rankings, (2) internationalization of higher education, (3) sustainability of higher education services, and (4) strategic direction of higher education. These four variables were dependently affected by eight (8) independent variables (institutional indicators), which are: (1) stability and the absence of violence from the political governance components, (2) international alliances, (3) equality in the provision of higher education services between sectors, (4) soft law as a component of informal governance, (5) technical efficiency, (6) expenditure gap, (7) government effectiveness, and (8) transaction cost in its informal measure of the cost of changing positions & believes (Appendix A).

The human development theme was formulated with two variables: (1) competitive capabilities of higher education graduates, and (2) knowledge producing and innovation. These variables are dependent on five (5) independent variables (institutional indicators) variables, they are: (1) stability and the absence of violence from the political governance components, (2) international alliances, (3) networks as a form of informal governance, (4) productive efficiency, (5) and cost of changing positions and believes as an informal component of transaction cost (Appendix A).

This is the last theme in our synthesis, it comprises of two dependent variables: (1) public commitment to social values & norms, and (2) driving collective behavior. These variables were dependently affected by three (3) independent variables (institutional indicators), which are: (1) soft law as a form of informal governance, (2) building cultural capital, and (3) forming institutional habitus (Appendix A).

In this paper we strive to answer four main research questions: (1) How can institutionalism facilitate the achievement of Saudi higher education goals?, (2) How can institutionalism enable the Saudi higher education sector to adapt to its internal and external environment?, (3) How can institutionalism enable integration of the Saudi higher education system?, and (4) How can institutionalism preserve cultural values and norms within the Saudi higher education sector?. And in light of the relations presented as a result of the review synthesis, that link factors of these research questions to the institutional indicators, we discuss herewith the validity of these relations by challenging them through a comparative view between the Saudi and the Swiss Higher education systems.

In this comparative view, the selection of Switzerland’s higher education system was based on a core indicator of its strength which is Switzerland achievement of the number one top country in the Human Development Index [72]. On that basis, the exploration of the higher education system in Switzerland became evident to serve as a verification model to the institutional indicators we explore in this paper.

In Switzerland, higher education is a responsibility shared between both the federal government and the cantons. This shared responsibility is governed through three main regulating orders: (1) the Federal Act on Funding and Coordination of the Swiss Higher Education Sector, which forms the legal basis at a federal level, (2) the Inter-cantonal Agreement on Higher Education, which forms the legal basis in the cantons, and (3) the agreement between the federal government and the cantons on Cooperation in the Higher Education Sector, which establishes a number of joint bodies and regulates their competences. Under this agreement, three bodies were established: (1) The Rectors’ Conference of the Swiss Universities; a body that represents the interests of Swiss universities at national and international level, It operates in two forms: the General Assembly, which sets the overall policy direction, and the Council of University Affairs, which oversees implementation, (2) The Swiss Conference of Higher Education Institutions; a body responsible for coordinating higher education activities throughout Switzerland, and (3) The Swiss Accreditation Council; which is an independent body responsible for quality assurance and accreditation in the Swiss higher education landscape [73].

For the purpose of this comparative, we analyze the Federal Act on Funding and Coordination of the Swiss Higher Education Sector being the legal basis on the federal level. This Act comprises of eleven chapters and eighty-one articles, the first articles, from 1 to 22, defines authority, tasks, and membership of the three central bodies responsible for the management of higher education and the councils and committees emanating from them. Afterwards, in articles 23 to 26, the Act clarifies the basis for admission to higher education institutions and the study structure. Subsequently, articles 27 to 35, lay down the foundations for quality control and monitoring, in matters such as teaching methods, research, and services provided by higher education institutions. The Act then moves on to articles 36 to 40 that lays down foundations for coordination in the entire Swiss higher education sector on priorities and financial and development plans at the national level. After that, the Act moves to articles 41 to 61 where economic matters and responsibilities between the federal government and the cantons are clarified. Afterwards, in articles 62 to 65, the Act states penalties and legal guarantees regarding the protection of university classifications and the awarded titles. In Article 66, the Act sets out the bases and authoritative means of collaboration in the international context. Finally, the Act sets out in articles 67 to 81 the provisions related to regulatory issues, as well as mechanisms for future amendments to the Act [74].

Aligning the mandates in the federal Act to the institutional structure and the indicators that comprise its four subsystems, we find, and as presented in Table 2 that some prominent indicators of the institutional concept are directly addressed, such as empowering the voice of social actors as an indicator to the institutionalism of the political system, while others, such as the effective Integration in the legal system is only partially apparent through the reference in the Federal Act to the consistency of the system’s provisions with relevant federal policies. And on the other hand, some prominent indicators of the institutional concept were not touched upon in any form, such as the equality between regions and sectors in the provisioning of higher education services.

| Institutional Structure | Institutional Indicators | Addressment of the Indicator in the Federal Act? | ||

| Fully | Partially | Absent | ||

|

Political System

(Goal Attainment) |

Voice of social actors | \(\sqrt{}\) | ||

| Political governance (voice accountability, political stability) | \(\sqrt{}\) | |||

| International alliances | \(\sqrt{}\) | |||

| Handling demand-supply gap | \(\sqrt{}\) | |||

| Equality in service provision between regions and sectors | \(\sqrt{}\) | |||

| Physical infrastructure alignement: assets facilities | \(\sqrt{}\) | |||

| Socio-economic state, political state, technical state alignment | \(\sqrt{}\) | |||

|

Institutional entrepreneurship (thru informal

means such as power interest groups. |

\(\sqrt{}\) | |||

| Institutional logic (thru informal means such as public opinion) | \(\sqrt{}\) | |||

| Informal governance (soft law, networks) | \(\sqrt{}\) | |||

|

Economic System

(Adaptation) |

Financial performance: Expenditure and investment gaps | \(\sqrt{}\) | ||

| Economic performance: technical, productive, allocative efficiencies | \(\sqrt{}\) | |||

| Economic governance (government effectiveness) | \(\sqrt{}\) | |||

| Formal aspects of transaction cost (e.g., cost of implicit attributes) | \(\sqrt{}\) | |||

|

Informal aspects of transaction cost (e.g.,

cost of changing ideological positions and beliefs) |

\(\sqrt{}\) | |||

| Complementary rules | \(\sqrt{}\) | |||

|

Legal System

(Integration) |

Effective integration in three levels of the legal system | \(\sqrt{}\) | ||

| Legal governance (rule of law, regularity quality, control of corruption) | \(\sqrt{}\) | |||

|

Cultural System

(Preserving cultural values) |

Forming institutional habitus (alignment with the social context) | \(\sqrt{}\) | ||

| Building cultural capital (thru informal means such as media) | \(\sqrt{}\) | |||

Looking into the institutional indicators in Table 2 as touched upon in the Swiss higher education Federal Act, we look herewith in more details at the four systems and how their indicators are embodied and acknowledged whether directly or indirectly. Starting with the political system, we present voice of social actors, which is one of the core institutional indicators to the political system, and we see it directly referenced in the Act in seven articles: 16, 17, 30, 33, 46, 52, and 59, with a prominent aspect of the right to representation, as all councils and committees include representatives from all stakeholders, article 13 is an excellent example of how this indicator is embodied, it lists all participatory representations whom take part in the Swiss conference of higher education meetings to act in an advisory capacity, representatives here include students, each level of the teaching staff (e.g., professors and lecturers), and trade unions and employers, and so forth. Another core embodiment of voice of social actors referenced in article 17 is the principle of “points”, which is used in decision-making by giving representatives of the cantons points proportional to the number of students in their cantons. And from another aspect of voice of social actors, particularly regarding funding, the federal government does not make these decisions without consulting the relevant bodies, this is stated in article 46 where the federal council takes the decision on eligibility for general funding after hearing the Plenary Assembly.

Moving to the economic system, we point out the concept of Reference Cost, mentioned in article 42 which addresses requirements for general funding, it is defined in article 44 as the expenditure required to provide high-quality education for each student, and it is calculated on the basis of the cost accounting records, further it is indicated that this cost should be adjusted periodically to ensure that adequate funding is secured to achieve the desired level of quality. Looking to this concept from an institutional perspective, we recall transaction cost and the cost of implicit attributes, the value of the attributes accompanying the leading service [44], and in the context here, the quality of education is an Implicit attribute accompanying education as the leading service, in other words, we see here that the Swiss Federal Act implicitly considers this aspect of transaction costs. We also note that the Act, in article 51 states that annual general funding is determined according to the educational and research performance, resembling the adoption of performance-based funding; which is central for promoting economic efficiency, a core indicator to the economic institutional system, it further sets the standards for how it is measured by looking into average study period, competitiveness, and the position of graduates in the labor market. The act further promotes economic efficiency in Article 47 by stating that entitlements for federal funding are increased once a higher education institute adopts cost-efficient practices and namely sharing infrastructure with other institutions, whether other higher education institutions or national non-educational institutions.

Looking into the legal system which is touched upon in some articles such as article 30, we see how authority is set to address issues such as ensuring the quality of education and ensuring that the institution meets the requirements of its mandate as a higher education institute. Enforcements of these aspects include monitoring admissions requirements, monitoring the eligibility of employees in different positions, monitoring the adherence to the mechanisms of participation in decision-making, and the mechanisms for equal opportunities and gender equality. The act builds this authoritative model further by looking to alignments supporting the global commitments such as aligning institutional mandates with economic, social, and environmental sustainability goals. All these measures are translated within the perspective of the institutional context of the legal system as embodiments of legal governance, promoting faces of regularity quality and rule of law.

The last system we discuss here is the cultural system, where we see from Table 2 that partial relevance was present in the Swiss Act. In article 59, forming an institutional habitus thru alignment with the social context was enabled, the Act promotes areas of national relevance, this includes support for linguistic diversity since Switzerland has three official national languages, and on that basis, the constitution gives the cantons the right to choose their official language [75]. In the Federal Law on National Languages, Article 15 states that the cantons must focus on their official language in education while encouraging linguistic diversity among learners, the goal is for students to master at least one other national language from a perspective of supporting multiculturalism and national integration, the federal government also provides financial incentives for activities that promote the national language, such as research publications and translated books [75]. In regards to the other informal indicator in the cultural system which is building cultural capital, we see that this indicator along with the other informal institutional indicators from the political and economic systems were not directly approached, however, in article 59, the Act acknowledges the right for funding for projects that serve national higher education policy interest, and lists areas of particular interest to the higher education system such as those contributing to the encouragement of sustainable development, student participation, equal opportunities, and so forth, and with this acknowledgment we have tagged the three informal institutional indicators from the political system: institutional entrepreneurship, institutional logic, and informal governance, and the one informal institutional indicators from the political system: the cost of changing ideologies and believes, and the remaining informal institutional indicators from the cultural system: building the cultural capital as partially addressed since the Act had addressed incentives for projects that contribute to the achievement national higher education policy interests.

We conclude our discussion of institutionalism in the Swiss Federal Act on Funding and Coordination of the Swiss Higher Education Sector by noting that 17 out of the 20 institutional indicators are either directly or partially present along the four systems, and thus indicates a high encapsulation of the institutional concept embodiment in the Swiss higher education system.

Moving comparatively to the local perspective, we investigate Saudi Arabia’s regulatory policies on higher education, and specifically the Universities Order being the latest order issued on higher education in the year 2019/1441 [76]. The 1441H Universities Order consists of 14 chapters and 58 articles. The first articles define the higher education system’s terminology and the entities responsible for university governance, management, and administration: the Board of Trustees, the University Council, and the President. Article 6 introduces the University Affairs Council, specifying its members, tasks, meetings, and secretariat. From Article 11 to 19, the Universities Order defines the Board of Trustees, its membership, and its tasks. This is followed by the Scientific Council (Article 20), the College or Institute Councils (Article 24), and the Department Councils (Article 27). Article 30 outlines the tasks of the University President and Vice Presidents, Deans and Vice Deans, and Department Heads. Article 40 addresses academic accreditation, followed by three articles on advisory councils and the university’s financial system (Articles 45–50). The system concludes with general and final provisions.

Following the same approach in review of the Swiss Federal Act against the institutional structure and its four subsystems, Table 3 showcases what institutional indicators are addressed and the level of their addressment in the Saudi Universities Order, where we see that none of the 20 institutional indicators of the four institutional subsystems were fully present, and only 5 were partially present, with the remaining 15 with no direct nor indirect addressment.

| Institutional Structure | Institutional Indicators | Addressment of the Indicator in the Federal Act? | ||

| Fully | Partially | Absent | ||

|

Political System

(Goal Attainment) |

Voice of social actors | \(\sqrt{}\) | ||

| Political governance (voice accountability, political stability) | \(\sqrt{}\) | |||

| International alliances | \(\sqrt{}\) | |||

| Handling demand-supply gap | \(\sqrt{}\) | |||

| Equality in service provision between regions and sectors | \(\sqrt{}\) | |||

| Physical infrastructure alignement: assets facilities | \(\sqrt{}\) | |||

| Socio-economic state, political state, technical state alignment | \(\sqrt{}\) | |||

|

Institutional entrepreneurship (thru informal

means such as power interest groups. |

\(\sqrt{}\) | |||

| Institutional logic (thru informal means such as public opinion) | \(\sqrt{}\) | |||

| Informal governance (soft law, networks) | \(\sqrt{}\) | |||

|

Economic System

(Adaptation) |

Financial performance: Expenditure and investment gaps | \(\sqrt{}\) | ||

| Economic performance: technical, productive, allocative efficiencies | \(\sqrt{}\) | |||

| Economic governance (government effectiveness) | \(\sqrt{}\) | |||

| Formal aspects of transaction cost (e.g., cost of implicit attributes) | \(\sqrt{}\) | |||

|

Informal aspects of transaction cost (e.g.,

cost of changing ideological positions and beliefs) |

\(\sqrt{}\) | |||

| Complementary rules | \(\sqrt{}\) | |||

|

Legal System

(Integration) |

Effective integration in three levels of the legal system | \(\sqrt{}\) | ||

| Legal governance (rule of law, regularity quality, control of corruption) | \(\sqrt{}\) | |||

|

Cultural System

(Preserving cultural values) |

Forming institutional habitus (alignment with the social context) | \(\sqrt{}\) | ||

| Building cultural capital (thru informal means such as media) | \(\sqrt{}\) | |||

Looking into the indicators of the political subsystem, and specifically the voice of social actor indicator, we find that although the Universities Order addresses the formation of a student council in Article 43, however, its formation is subject to the Board of Trustees, and thus students as social actors in the higher education system may channel their voice if the Board of Trustees formulates this council, unlike the Swiss Federal Act where the right to representation is mandated in all councils and committees, with representation of not only students and members from within the higher education system but all stakeholders of higher education system such as trade unions and employers. Another note worth mentioning in this context is how decision is taken if voting parties on an issue come to a tie, and according to Article 14, in this case the decision will follow the party that the president voted with, another difference from the Swiss Federal Act where the principle of “points” is applied, by giving representatives of the cantons points proportional to the number of students in their cantons and thus a weighing system reflected on decision making with relation to the number of students instead of authority or title.

Moving to the economic system, which is addressed in the Universities Order from a new perspective with the regulation of the university’s financial and administrative independence, more focus is placed on financial affairs in Chapter 13 of the Order with 6 Articles however, other than the auditory perspective on budgeting and spending in Articles 46 & 47, and the identification of financial resources in Articles 49 & 50, which are considered as partial addressment of economic measures of efficiency and effectiveness, there were no addressment of mechanisms or incentives that shape and direct financial support in comparison to the Swiss Federal Act that linked federal funding to performance and instated incentive measures to federal funding as well.

The legal system in the Saudi Universities Order fell short with no addressment to any of its institutional indicators compared to the Swiss Federal Act that emphasizes regulatory oversight to promote good governance indicators (Rule of law, regularity quality, and control of corruption), this was apparent in Article 30 of the Federal Act where authority measures were set to audit many aspects, one of which is quality control and accreditation, an aspect with a dedicated chapter and 9 articles governing rights, requirements, and control for both program and institutional accreditations (Chapter 13), whereas the Saudi Universities Order dedicates two articles to accreditation (40 & 41), where accreditation is ordered on both a program and an institutional level to the responsibility of the university however no system-driven oversight role is addressed to any of the accreditation practices and rights.

Moving to the last subsystem; the Cultural system, the Saudi Universities Order mentions in Article 54 the official language in teaching, which is the Arabic language, and thus we consider this as one alignment with the social context, although there were no incentives for research and publication in Arabic with this mandate in comparison to the Swiss Federal Act, there were also no other addressment of any cultural or social engagement rights or reflections, similar to what AlGhamdi [77] had proposed in her study to elevate community bond such as raising and directing cultural behavior and social values, which is a perspective that was partially taken in consideration in the Swiss Federal Act in Article 59 by addressing funding for project that serves national interests.

In closing this review of the institutional indicators in the Saudi Universities Order, we find that 5 out of the 20 institutional indicators are partially present along the four systems with no indicator with direct addressment, however, it is the right to state that this review only explored the core document of the 1440H Universities Order and did not include any extended regulation related to this core order that might have of complemented the institutional embodiment of the system as a whole. What was presented is a preliminary comparison between the international dimension and the local context regarding the basic system governing the higher education system.

A core limitation of this study is the regulatory scope included in the comparison, in both the Swiss and the Saudi context, only one document was put under the analysis and review which is the core document regulating Higher Education in the country and that denotes that extended regulations and guiding procedures which could have complemented the institutional embodiment of the system as a whole were not accounted for, a case that could support the Saudi context knowing that the Universities Order has more than 15 regulatory appendices detailing issues of university financials, post graduate education, scientific associations, and so forth [78].

Another limitation of the study is the absence of a scientific mean to validate the institutional indicators that we have proposed herewith by building on Parsons Social Action System theory [11], which should be investigated by future research to better formulate and refine a solid institutional structure that can guide institutional enactments and practices in any organizational domain.

It is well established that institutional practices are core to achieving organizational goals [8,12], and it is well established that Education must exist as a distinct institution that deals with formal and informal norms of social needs, as education is called “a sub-system of society” [10], and thus rooting institutionalism from an organizational perspective to the Social Action System theory is one way to methodologically direct enactments of institutionalism on the basis of the GAIL system being a system that comprehends the four core elements of any social unit, politically, economically, legally, and culturally.