The study’s relevance is determined by a sharp increase in interethnic and intercultural conflicts due to the digitalisation and mediatisation of geopolitics. Socio-communicative channels of ideological influence on ethnocultural life make it possible to actively manipulate people’s desire to preserve their ethnocultural identity, supporting extra-legal forms of institutional social management implemented through media, which requires deep investigation and comprehension. The article aims to outline the role and place of media and the media market in today’s geopolitical conflict landscape, both on a global scale and at the nation-state level, based on research on the conflict potential of media within ethnic and cultural identity patterns, their shaping and functioning. The research is founded on concepts and hypotheses developed in national-cultural identity, globalisation, and geopolitics. It is also based on methodological approaches such as civilisational, comparative, systemic, dialectical, sociocultural, and synergetic. It is shown that media products and the media market are a resource for ethnic conflict mobilisation. Social actors in mass communication strive to convince society of the benefits of their peace/conflict projects. It was revealed that contemporary communication, media and journalism studies have mostly neglected to critically assess the news media’s role in producing and distributing propaganda based on ethnic and cultural identity narratives, and the necessity of filling this research gap is emphasised. It has been demonstrated that information influences can change the main geopolitical potential of the state – the national mentality, culture and moral state of people. The media market today has become a full-fledged element of postclassical geopolitics. The question of the role of the symbolic capital of culture in the information (media) space is now acquiring not an abstract theoretical but a strategic geopolitical significance.

The era of globalisation at the turn of the 20th and 21st centuries, spreading stereotypes of “universal” values and lifestyles, simultaneously intensified the processes of studying ethnic culture and national identity. Ethnic culture and ways to preserve identity as a unique cultural marker of social action attract the attention of researchers from different fields of knowledge: cultural scientists and historians, philosophers and sociologists, art historians, psychologists, etc.

Modern globalisation, regionalisation, and glocalisation in the development of the global world system have determined multi-vector social processes in the ethnocultural sphere. As a result of the development of dialectically interconnected processes of globalisation, regionalisation, and localisation in the geoeconomic, geopolitical, and geocultural subsystems of the global world system, the formation of the global information space of the Internet, asymmetry in the distribution of information is being overcome. Information accessibility is increasing, which determines sociocultural assimilation, hybridisation, and separation processes. These processes are developing under the influence of increased international competition, geopolitical cataclysms, and clashes with the geoeconomic interests of global players in the world commodity markets and producers of goods and services.

At the same time, socio-communicative channels of ideological influence on ethnocultural life make it possible to actively manipulate people’s desire to preserve their ethnocultural identity, supporting extra-legal forms of institutional social management. Such channels, of course, include the media.

The viability of traditional ethnic culture in modern society often comes down to only a discussion of the functioning of the language and the popularisation of the cultural heritage of various ethnic groups in the new communicative environment. Meanwhile, the problem of a person’s ethnic self-determination in new cultural conditions is equally important to the language issue when discussing the transformation of ethnic culture in modern conditions. The new sociocultural reality gives rise to the need for a person to search for other forms of representing his identity, different from the usual ones because the cultural space has changed, – the Internet, communications, and the media sphere have begun to play a significant role. It is also necessary to understand that in the modern world, ethnic identity does not die out; this criterion is again becoming a basic one. Therefore, the search for ethnic self-expression, new opportunities and options presented by the media is natural.

The main characteristic of the modern era is not only the assimilation of the highest achievements of the cultural and educational values of humanity but also a gradual, conscious process of ethnocultural revival, which researchers rightly call “ethnic renaissance”. A characteristic feature of this period is the extraordinary influence of ethnic and mass culture on personality formation. Today, two contradictory trends in the development of civilisation have emerged: on the one hand, the creation of global structures, and on the other, the segmentation of the world. Moreover, as soon as one tendency strengthens, another becomes active simultaneously [1].

At the same time, media, media products, and the media market represent “a resource for ethnic conflict mobilization” [2]. Social actors in mass communication strive to convince society of the benefits of their peace/conflict projects and the need to achieve an acceptable peace. The struggle of influence groups for the dominance of their peace/conflict projects is carried out within the framework of such thematic fields of mass consciousness as the sphere of attitude towards the history of one’s ethnic group and the history of neighbouring countries, the sphere of interpretation of state policy as aimed at fencing/globalisation, the sphere of interpretation of international relations and the sphere of formation of attitudes of interpersonal situational communication with foreign ethnic/national groups.

In turn, cultural identity describes a collection of attributes associated with specific populations that are sometimes assumed to be constant but vary with time. Throughout history, mass media have been instrumental in moulding national cultures and cultural identities. Within the global system of nation-states, the influence of the press, movies, radio, and television has been felt firsthand on national identities and cultures. When official institutions, the country’s dominant economy, and society work to eradicate a minority group’s cultural identity, cultural genocide may be taking place. It might be inert if the dominant institutions let the linguistic, demographic, or economic forces created by earlier actions have their natural course. If minorities do not resist, minority identities could be destroyed in both situations.

Mann [3] rightly claims that the construction of ethnic identity represents a multi-dimensional phenomenon, including biological, psychological, social, cultural, and political interaction. Ethnicity develops through group experiences, geographic limitations, biological imperatives, and political aspirations, starting with the relationship between an infant, mother, and family. Intercultural contacts play an equally crucial role in various explanations of ethnic identity. Indeed, as cultural minorities fight to overcome oppression and realise the fundamental human right to self-determination, the collision of cultures can be a significant factor in the formation of ethnic identities.

Thus, ethnic and cultural identity are inseparable. Thus, any influence on one of them inevitably influences the other [4]. However, under the influence of globalisation and complex socio-political processes on a regional scale and within nation-states, these two components acquire the property of emergence, as a result of which identity as a system can receive very unusual properties, – in particular, indigenous ethnic identity can be combined entirely with “McDonaldized” consumer culture. At the same time, this emergence generates more significant potential for conflict. “Hybridised” identity is actively used by the media for commercial and political purposes, often catalysing destructive processes.

The conflict-generating potential of the media sphere is difficult to overestimate; the conflict of values and identity is one of the most severe forms of actualisation of contradictions between subjects of conflict interaction [5]. The sphere of reproduction of cultural goods is resourceful regarding conflict potential because it opens up enormous opportunities for cultural expansion, which develops into influence and, therefore, into a threat to cultural sovereignty [6]. The place of the media sphere in this system is prominent; it can act as an intermediary between the producer of a cultural or information product-text and the recipient, moreover having an extraterritorial nature. The implementation of strategies for the cultural self-identification of nations and peoples is forced to meet with the tendency towards the internationalisation of cultures within the framework of globalism, which may lead to the emergence of acute contradictions and, subsequently, conflict.

Modern mass media themselves represent a powerful tool for shaping public opinion and, accordingly, are often used by political-economic elites as a tool of manipulation and suggestion [7]. The study of the landscape of the modern media market, the behaviour of its players and objects, the vectors of the balance of power, and the conflict potential represents today a very pressing scientific task, which needs to be solved not only in the plane of media studies and ethnic research but also geopolitics.

Representatives of primordialism recognise ethnicity as an objective fact, an eternal characteristic of humanity. Within the framework of the primordial paradigm, ethnos express transformations of primordial and unchanging, biologically and socially determined connections. According to some researchers, this understanding does not consider changes in linguistic, religious, and gender identities that occur during a person’s life and are significant for social connections [8]. The facts of migration and interethnic processes show that ethnic communities are not original, unchanging and isolated entities. National identity is seen as a “collective sense of loyalty”, “an attachment arising from a sense of natural spiritual affinity” [9].

The instrumentalist approach views ethnicity as the result of political myths created and used by cultural elites in their quest for advantage and power. Ethnicity emerges from elites’ competition within boundaries determined by political and economic realities [10]. In a mass culture society built on the values of consumption and pragmatism, ethnicity is a means of stratifying social groups. Ethnocultural identity appears as an indicator of social mobility. It allows gaining status and confirming the priority of the interests of the individual. People consciously mobilise ethnic symbols to achieve their goals. Ethnicity is thus understood as the result of the mobilisation of social groups by the political class.

Within the framework of the constructivist paradigm, conditioned by the principles of neo-Kantianism, “philosophy of life”, post-structuralism, an ethnic group is described by socio-psychological characteristics. The essential characteristics of social groups result from the differences between community members [11-14]. Ethnic communities, from the constructivists’ point of view, always exist within the framework of intergroup interaction. Ethnicity is considered an intellectual construct that spreads among the masses through belonging to a particular group. Common origin, language, and culture are essential signs of ethnicity but not eternal. They are the simulated result of the deliberate efforts of writers, scientists, and politicians.

An intermediate position between primordialism and constructivism is occupied by ethno-symbolism, the most authoritative theorist of which is E. Smith [15]. According to the theory of ethno-symbolism, even in the pre-industrial era, many ethnic communities arose, representing populations with typical elements of culture, historical memories, myths about common ancestors and a certain degree of solidarity. Some of these communities moved to a new level of cultural and economic integration and standardisation, became tied to a specific historical territory and developed their laws and customs. They became a kind of “ethnic core” around which the population was concentrated, that perceives these myths, traditions, solidarity, and cultural norms as their own [16].

In 2000, Cottle observed that the media play a significant role in the public representation of uneven social relations and the exercise of cultural power. Members of the public are, for instance, invited to build a sense of who “we” are and who “we” are not through representations, whether as “us” and “them”, “insider” and “outsider”, “colonizer” and “colonized”, “citizen” and “foreigner”, “normal” and “deviant”, “friend” and “foe”, “the west” and “the rest”. Through such tactics, the social interests mobilised across society are distinguished, made unique, and frequently exposed to discrimination. However, the media can also support social and cultural variety and create vital spaces where imposed identities or other people’s interests can be contested, opposed, and altered. The media landscape of today is evolving quickly [17].

Behm-Morawitz [18] asserts that racial and ethnic representations in the media are abundant and can shape people’s opinions of themselves. People contribute to and consume the media’s portrayal of race and ethnicity. These representations impact the formation of racial and ethnic identities through various psychological mechanisms, such as social comparison and classification. We connect with similar and dissimilar people through mediated contexts like television, movies, video games, social media, and nonmediated interpersonal and group-based interactions [19,20]. These mediated experiences influence our identity development in various domains, including racial and ethnic identity.

We usually process racial and ethnic experiences and depictions through media in a subliminal way. The way we think about racial and ethnic identities, including our own, can be influenced by the media. The presence and absence of racial or ethnic people, as well as the portrayals of those people, convey implicit messages about race and ethnicity more frequently than explicit discussions of these topics through media channels. It has been demonstrated that the stereotyping of racial and ethnic minorities in the media has a detrimental effect on how people view those individuals in real life. Through several cognitive processes, these mediated representations contribute to the establishment of racial and ethnic identities.

According to Behm-Morawitz [18], a person’s exposure to media messages on race or ethnicity might cause preconceptions about that group to come to life. Similar to the stereotype threat instance mentioned earlier, media information has the power to reinforce negative stereotypes about a person’s race or ethnic group. This could happen when consuming news, entertainment, or social media. A racial or ethnic stereotype is successfully retrieved from memory storage and activated by media priming.

However, the powerful conflict-generating potential of the media in an ethnic context has been realised relatively recently and is insufficiently studied. Surprisingly, the Rwandan experience has not triggered a surge in research in this area. Speaking about the role of information influence in an ethnopolitical conflict, it seems helpful to cite the example of the civil war in Yugoslavia, when in the summer of 1997, the peace process in Bosnia was in danger of breaking down. Diplomacy and threats of military intervention were unable to reverse the situation. On television channels controlled by Serbian nationalists, international peacekeeping forces were increasingly referred to as “occupiers”. For example, images of NATO tanks were interspersed with archival material from World War II showing the Nazi occupation. As a result, tensions grew. However, international forces decided to suppress unwanted propaganda using military equipment. Within weeks, international peacekeeping forces in Bosnia had occupied vital television and radio broadcast centres, driving the worst offenders off the air. However, in the parliamentary elections that soon took place in the Bosnian Serb Republic, extreme nationalists retained their positions, although the broadcast of their chauvinistic propaganda was significantly limited [21]. These are the long-term effects of media propaganda emphasising differences in ethnic and cultural identity. Moving these narratives into the commercial media sphere and integrating them into a commercial media product increases the latency of the conflict potential and, at the same time, enhances its effectiveness.

The theoretical and methodological basis of the study is made up of general scientific principles of theoretical research: objectivity, scientific character, and unity of the logical and historical. The research is founded on concepts and hypotheses contained in the works of modern scientists on the problems of national-cultural identity, globalisation, and geopolitics. The research is also based on methodological approaches such as civilisational, comparative, systemic, dialectical, sociocultural, and synergetic. The study employed systematic approaches, comparative analysis, and a specific historical approach.

In the modern world, ethnic and national aspects play a vital role in the context of the national security of states, in particular, in ensuring the stability of political systems and overcoming several internal political crises, the genesis of which in multi-ethnic states is often conflicted on an interethnic and international basis. In the 19th century, many researchers, while thinking about the future formation of the international space, were confident that nations and ethnic groups would soon become a kind of rudiment in the history of humanity under the influence of such global processes as industrialisation, modernisation, and globalisation [22]. However, the realities of today prove the opposite picture of the world, which is characterised as never before by high growth in the ethnic and national identification of citizens. All the diversity of existing ethnic groups, peoples, and nations everywhere declare their own choice of their vector of development and self-identification, as well as dialogue as collective or individual actors, during which they can transform their identity and the further path of their development. The problem of resolving ethnopolitical conflicts and contradictions is a primary task for all states in ensuring national security and sustainable development. That is why the development of the concept of national security of states deserves a clear and detailed study of such categories as ethnicity and nation, which should be carried out based on a comprehensive analysis of the institution of national-ethnic relations and the development of that level of national-ethnic tolerance in the most conflict-prone areas inhabited by ethnic communities, which can prevent contradictions and latent conflicts for the stable development of the state.

When analysing and studying ethnopolitical processes, most researchers need to pay more attention to the influence of geopolitical factors. Research that, to one degree or another, reveals that the problems of ethnopolitical processes often come down to socio-economic factors or the problem of nation-building in general. At the same time, when studying such processes on the territory of states, the geopolitical motives of ethnopolitical relationships are ignored. For example, the role of ethnogeographical factors that come to the fore when considering ethnopolitical processes at the level of intercivilizational – that is, intercultural confrontation – is downplayed. Accordingly, ethnic and cultural identities are not considered as a single system, and the role of the media market in its formation is still not given due attention.

The development of network information structures and the emergence of virtual space have forced us to take a fresh look at the problem of organising and protecting political space in geopolitics. While the classical geopolitics of everyday life is based on sacred ideas of faith, soil, and blood, the postclassical picture of political space raised the question of translating these symbols into virtual space in the form of the symbolic capital of national culture. While in the industrial era, the aggressor sought to seize territory, destroying industry and means of production, in the information society, the primary means of control over space became control over the individual (personality) – managing the worldview of entire peoples; the struggle for space takes place in the information field this is where the cutting edge of postclassical geopolitics is [23].

The new realities of the information society have posed an unconventional task for geopoliticians: to analyse the influence of information impacts on solving problems at the geopolitical level. Today, it is evident that namely information influences can change the main geopolitical potential of the state, – the national mentality, culture, and moral state of people; thus, the question of the role of the symbolic capital of culture in the information space is now acquiring not an abstract theoretical, but a strategic geopolitical significance.

The modern global information space, in which the Internet, mass media, and advertising reign, is a world governed by information. “The invisible hands of hidden information influence shape the contours of the future world” [24]. Communication channels worldwide, including (and especially) the media market, are becoming a virtual power arena of geopolitical struggle, which is invisible at first glance. Today, it is evident that the most critical information revolution took place behind the scenes in the media. It was associated with the emergence of information and psychological weapons capable of effectively influencing people’s psyche, emotions, and moral state. Geopolitics is beginning to explore the new virtual information space actively, and the results of this exploration can, without exaggeration, be called revolutionary.

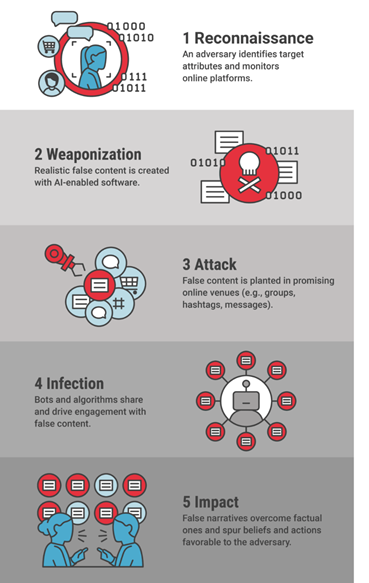

There are now more players and advanced tactics in the digital battlefield. According to the CBInsights journal, which focuses on the future of information warfare, citizens will soon find themselves in the digital crossfire of international battles that exploit internet platforms with persuasive disinformation campaigns. The vision of this future is depicted in Figure 1 below.

Among these new conditions, journalism emerges as an actor in the international system in the sense that the agenda that is put forward based on an analysis of the realities of the media widely highlights the problem, arouses international interest in it and, to some extent, represents the impetus for its solution [26]. Moreover, journalists’ approach to events determines the interpretation of the problem, which in the geopolitical “game” is essential in forming centres of power. At the same time, the “field” for geopolitical games is often nation-states and proxy wars often become tools.

At one time, US President Dwight Eisenhower defined proxy wars as “wars fought by the hands of others” [27]. The classic definition of a proxy war was given by the American political scientist Karl Deutsch in 1964: “A proxy war is an international conflict between two countries that are trying to achieve their own goals through military actions taking place on the territory and using the resources of a third country, under the guise of resolving an internal conflict in this third country” [27].

At its core, a proxy war is a civil war that is either provoked by a foreign state or a third party to the conflict or is waged with its active resource, political, and military support. In the modern world, the widespread occurrence of proxy wars is directly related to the emergence and proliferation of nuclear weapons. The use of these weapons is fraught with catastrophic consequences for participants in a nuclear conflict. Therefore, the nuclear powers have made and are trying to prevent direct regular military action among themselves.

In this regard, the history of the Indo-Pakistani conflicts is characteristic. Since the last direct Indo-Pakistani war in 1971, both countries have developed or acquired nuclear weapons. Now, the hostilities between India and Pakistan are being fought in the form of proxy wars. At the same time, the ‘great powers’ are doing everything to prevent a direct nuclear clash between India and Pakistan.

Syria has become the most severe ‘testing ground’ for a regional proxy war, the properties and techniques of which have yet to be analysed. On the surface, the war in Syria has become a war between Muslims of different directions, – Sunnis and Shiites. The existing contradictions in society, including confessional and regional ones, served only as the initial combustible material for the manifestation of social protest, which was very quickly translated into the most radical form of armed confrontation. Social protest in Syria, as in all countries of the “Arab Spring”, was used in the struggle for power and obtaining political preferences. The interfaith nature of the conflict in Syria acts only as a socio-psychological factor, a flag for identifying the parties and mobilising supporters within the “conflict territory” and beyond [22].

According to Tourmani [28], social media was crucial to the success of the Syrian revolt since it facilitated the development of the demonstrators’ demands and status as well as their organisation and communication.

To obtain the necessary public support, the parties are trying to interpret further options for developing events in different ways with the help of the media. A lot depends on whether the country’s population will support the sending of additional aid or troops, how residents of other countries will react to the further continuation of the conflict, or what representatives of international organisations will answer when asked about the legitimacy of specific steps. The formation of public opinion by various countries is aimed at obtaining approval of their policies from the population and the necessary support for further actions.

People living in regions of proxy wars often experience dire consequences. Homes are destroyed, lives are lost, and infrastructure is destroyed, leading to long-term social problems. That is why the international community is trying to find ways to end such conflicts. However, the difficulty is that many proxy wars are not officially recognised. Thus, determining who is behind the parties’ support of the conflict is often difficult.

Proxy wars reflect the modern world in their way. Globalisation and countries’ connectedness have made direct wars between major powers rare. However, implicit opposition and support for local conflicts, mainly through media use, have become commonplace. In these conditions, strategy and tactics precede power and direct military conflict. However, proxy wars remain dangerous and can have a global effect without declaring war between major powers.

The unleashing of proxy wars is often carried out based on artificial catalysation of smouldering social conflicts precisely with the help of powerful media “campaigns”, deployed progressively – first, the “seeds” of interethnic/intercultural conflict are thrown in. Then, increasingly heavy “artillery” is used in an extreme form similar to the media “strategies” of the genocide in Rwanda.

The twentieth century demonstrated rather negative examples of the use of media as catalysts for armed conflicts and world wars. The actual understanding of the problem of mass media’s impact on audiences within the framework of the sociology of mass communications emerging in the 20s of the last century began with a statement of the defenselessness of the individual and public opinion as a whole before the mouthpiece of the mass media (MSC). As sociologists note, during the First World War, the propaganda apparatus of the warring countries used the full power of an extensive press. “Newspapers dragged us into the war”, as described by Kamalipour et al. [21]. The age-old but no less effective strategy of national and state elites to mobilise the masses in conflict to distract from internal political problems and achieve social solidarity based on hostility towards an external enemy has received a fantastically effective tool in the form of the mass media. In the 30s, the propaganda machine of totalitarian states brought the tactics of manipulating consciousness in order to inflate racial and class intolerance, xenophobia, and aggressiveness to “perfection”. During the Weimar Republic, Germany’s defeat in the war was determined, not without the help of newspapers, as the cause of the economic crisis and life difficulties of the ordinary population, and the energy of social discontent was redirected into demands for revenge.

As it is known, namely the media played a decisive role in the massacres of the population of Rwanda. Media representatives deliberately incited tribal hatred and openly called for violence and massacres. Key roles were played by the newspaper Kangura, the state-run Radio Rwanda, and the private radio station Thousand Hills. Live radio presenters used the word “inyenzi” – cockroaches – to refer to Tutsi. Slogans were heard daily: “Work, work, the graves are not full yet!” The Rwandan government has deliberately used the media as a weapon of mass destruction. Due to their reach, propaganda slogans sounded in every home. The Hutus received explicit instructions to exterminate the Tutsis, as well as approval for such actions. Propagandists presented cruelty and violence as the only method of struggle for survival. A few years later, the International Tribunal for Rwanda tried the organisers and instigators of the genocide. Journalists who called for violence and officials who used the media to incite conflict were punished [29].

Another effective method of increasing hostility and narrowing communication contacts is ethnic or national fencing. Own ethnic group or country is considered superior to all other ethnic groups or cultures, accordingly viewed as inferior or potentially hostile. Thanks to the suggestive influence of the mass media, the population has the impression of being surrounded by a ring of enemies. The ideas of racial superiority and ethnic fencing through the prevention of interracial marriages were most clearly expressed in Nazi ideology. They were successfully broadcast through German newspapers and the press. However, in one form or another, they were present in the information field and politics of all countries of the Hitler coalition. The illusion of being surrounded by enemies along the entire perimeter of the borders is still successfully constructed in the minds of audiences in rogue countries, such as North Korea.

Stigmatisation based on ethnicity or class is another effective means of catalysing conflict behaviour. Intensifying national intolerance towards “foreigners” and designating certain ethnic minorities as “scapegoats” is a standard method of escalating conflicts, often implemented with the help of the media. This method of “labelling” inevitably leads to mutual alienation and increased hostility between the dominant ethnic group and ethnic minorities.

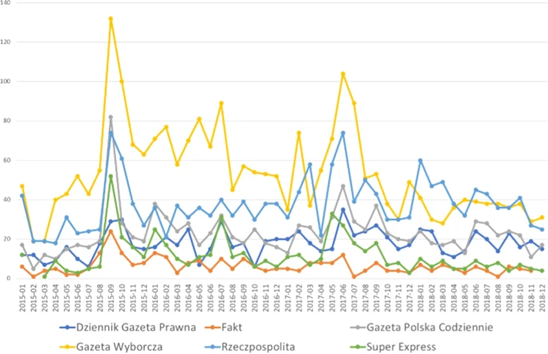

The contrasting views on migration expressed by the Polish media between 2015 and 2018 are detailed by Troszyński and El-Ghamari [30]. Press, television, and Internet surveillance were the foundation for the media content analysis. The number of newspaper stories, online articles, and TV broadcasts on migration for 2015–2018 is displayed in the graph below (Figure 2). The analyses found a clear difference between liberal and conservative discourses. These variations in topic matter, tone, and attitude were evident in the descriptions of the migratory crisis. The conservative media exclusively covered the opposing sides of migration; if Poland did not have such problems, they shifted their focus to rallies against immigration throughout Europe. The liberal media has been emphasising the need for sympathy with migrants and highlighting the unique nature of migration to Poland, namely from Ukraine. However, the primary distinction was each media outlet’s political inclinations. Based on this exact factor, the writers have illustrated differences in media coverage. Political parties were not linked to tabloid reporting, which attacked both the opposition and the government’s policies. The securitisation of migration, however, is the most crucial viewpoint from which Troszyński and El-Ghamari [30] characterise the information gathered. Regardless of political differences, the topic of security is covered in every conversation that has been examined. However, the research indicates that the right-wing press emphasises the seriousness of threats.

The myth of the “besieged fortress”, constructed and transmitted to the masses using controlled media, includes historical and patriotic mythological narratives, an attitude towards identification with a stereotypical positive reference group, and a stereotypical image of the enemy [31].

Within the framework of mass culture, the image of the enemy sometimes acquires caricatured, clichéd features as part of the media market’s products.

One of the fundamental human needs is belonging to an ethnic community. Personal identification processes cannot be done without awareness of inclusion in the sociocultural paradigm of an ethnic group. This mainly irrational process is a source of conflicts that arise, as a rule, based on a violation of identification processes. Scholars define ethnic conflict as any competition between groups, – from actual competition over the possession of scarce resources to perceived divergence of interests – whenever at least one of the parties perceives the opposing party to be defined in terms of the ethnicity of its members [17].

The conflict-prone nature of the processes of ethnic identification forces the media to pay increasingly close attention to this topic. Media representatives must actively disseminate information consisting of stereotypes, facts, and ideas. Thus, in the minds of readers, viewers, and listeners, they form specific images, opinions, and attitudes (not always correct) on specific issues. In most cases, communicators pursue a specific goal by conveying specially prepared information to the audience. Using various propaganda techniques and methods, modern mass media create their reality: they can attract attention to an event or phenomenon, turn it into a sensation, and distract them.

Ethnic stereotypes are usually related to perception. Arising spontaneously, they do not always correlate with experience, but they influence the formation of new experiences, even if it is false. Another distinctive feature of ethnic stereotypes is stability with possible variability over time. In the 21st century, when the identity crisis continues to be a reality for most countries of the world, the mass media use the method of stereotyping to protect ethnic identity. It is evident that a person always perceives “own” as “familiar, close” and “alien” as “unfamiliar”. The first is perceived positively, and the second is often wary, sometimes hostile. Professional journalists, to preserve the ethnic identity of one group, broadcast to the audience information that distorts reality regarding another group, using the “us-them” opposition, which is observed in the mass media increasingly more often.

When an ethnic conflict arises, negative ethnic stereotypes are used in the mass media in order to consolidate the “enemy image”, dehumanise the opponent and take him beyond the framework of universal norms and principles [32,33]. Forming the basis of propaganda, stereotyping allows interested circles to manipulate public consciousness with the help of the media, introduce false myths into it, and spread prejudices against the antagonistic ethnic group.

In Australia, the media has emerged as a significant area of concern in several government investigations into racism and racial relations. As a result, the Inquiry into Black Deaths in Custody, a four-year effort that looked at more than a hundred examples of Aboriginal people dying in jail or under police custody, suggested taking quick action to enhance media coverage of Aboriginal people living with white people. Proposals included a significant overhaul of the racial curriculum at journalism schools. The National Inquiry into Racist Violence also discovered that the public was gravely underinformed about the variety of experiences because of the media’s critical role in stifling contact between racial and ethnic groups. Although some rural communities’ specific newspapers were identified as significant causes of the rise in local interracial friction, the article’s central thesis was that the media did not adequately represent diversity and only covered minorities when they became a threat to the established social order or value system. Additionally, it advocated affirmative action plans to place members of minority communities in mainstream media positions and suggested steps to enhance the education and training of journalists [29].

It is not unexpected to find these similar values preached throughout the bureaucracy, given the formal government commitment to multiculturalism regarding cultural diversity and reconciliation about settler/Indigenous people ties. The national government mandates that its media adhere to Equal Employment Opportunity, Affirmative Action, and merit-based hiring practices for women. It also mandates that principles of Access and Equity be followed when providing services and attending to the needs of customers and clientele within the public sector. These guidelines can be challenging to put into practice since there has been constant criticism that the guiding principles included in the programs and the standards for proper behaviour contain presumptions that prejudice members of marginalised ethnic groups. The more those individuals deviate from the standards of the majority in terms of colour, language, accent, cultural practices, and belief systems, the more challenging it will be for them to fit in with the unwritten guidelines that decision-makers follow.

Lastly, it is essential to consider the idea of cultural genocide, which can only be carried out in the modern era through the media. There are various ways in which cultural genocide varies from physical genocide. Firstly, cultural genocide destroys a person’s soul, community, and way of life; physical genocide results in death. Second, in order to commit physical genocide, a dominant group must actively participate in the effort to wipe out the minority physically. Cultural genocide frequently happens without much conscious involvement. The minority group may be destroyed by objective factors such as economic, demographic, or linguistic ones, which the dominant group may support or merely permit. Third, a government commits physical genocide as a matter of national policy. Non-state organisations like the media, land developers, and international companies may even actively promote cultural genocide. Cultural genocide differs from physical genocide in that it is more subtle and less brutal due to each of these factors. However, when minorities and Indigenous people are forced to become “modern”, losing the characteristics that make them unique, distinctive, or a cultural or national entity, it has become a powerful force in many parts of the world [34]. However, this ‘mild’ form of genocide quite effectively allows for achieving geopolitical goals.

The media market has developed into a significant player in today’s geopolitical environment, with the power to influence social relationships, proper social discourse, and ethnic and cultural identity. Today, we see “broadcasting power in the age of information” [35]. One such instance is how Al Jazeera Network facilitated Qatar’s transition from a microstate to a major geopolitical player. Just fifteen years ago, Qatar was on the verge of becoming a colony of Iran or the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Today, it is a significant player in the region’s ongoing religious and political disputes.

The information paradigm of geopolitics, implemented through the landscape of the media market, sees the primary goal of geopolitical technologies in changing a person, his worldview and identity; the central anthropological problem of geopolitics in the new conditions is the influence of virtual media reality on the formation of the mentality of a person in a political information society, influencing patterns of ethnic and cultural identity [36]. Information wars use the destructive effects of information technologies, which enhance the “anatomy of human destructiveness” [37]. Military experts define information-psychological weapons as “non-lethal weapons of mass destruction” capable of providing a decisive strategic advantage over a potential adversary [38]; its main advantage over other means of destruction is that it does not fall under the concept of aggression accepted by international standards. Modern geopolitics has yet to solve the complex problem of control over information weapons, which calls into question the very existence of man. New information technologies, if considered weapons, can turn into a total disaster for humanity since, as a political instrument, information warfare means the existence of one society at the cost of the destruction of another. The problem of using information and psychological weapons in the information space remains open today. While in traditional spaces, – land, water, and air, – the boundaries and rules of civilised behaviour have long been defined by international documents and agreements and are at least to some extent controlled by the UN Security Council (although, as many examples from the 1990s–2000s show, this control is ineffective), in the information space anarchy now reigns.

Most modern communication, media, and journalism studies still need to critically evaluate how the news media contributes to creating and disseminating propaganda. Scholarly treatises on the news media hardly ever use the term propaganda, despite the news media’s incorporation into the state-corporate nexus. Additionally, very few academics have worked to develop a methodical understanding of the various propaganda strategies currently used in liberal democracies. Filling this research gap is an urgent task for prospective scientific studies and an agenda for broad public discourse.